- Home

- Alison Hart

Gabriel's Horses Page 7

Gabriel's Horses Read online

Page 7

Suddenly the wagon is surrounded with women begging us to tell recruits Ames, Elijah, or Quincy that their families are starving. Jackson and I repeat names, news, and pleas for help and take a few letters. Before leaving, we pass out the rest of Ma’s biscuits and sweet potato pies. When we set off, the children are fighting over the food while the women gaze forlornly after us.

I stare back at them until we round a corner, never having seen hunger like that before. Master Giles believes a working hand needs a full belly. “Those women and children are starving,” I say to Jackson. “Yet it’s summer, and crops alongside the road appear plentiful.”

Jackson snorts. “That don’t mean food is plentiful for all. If those women back there take crops from the fields, they’ll be whipped for stealing. And even on a farm when there is enough food, slaves still starve. I been on places where the master eats roast chicken and ham, biscuits and bread, peaches and pies in one sitting while the slaves get nothing but cornbread and mush.”

“But those women ain’t slaves,” I point out.

“They might be runaways,” he explains with a shrug. “Women who followed their men to Camp Nelson. I don’t know for sure, Gabriel. One thing I do know, though, life ain’t never easy for colored folk.” He winks at me. “Unless you a winning jockey in Saratoga. Then you be counting your money every night.”

I face front, not wanting to talk about his leaving. Ahead of us, two soldiers in blue uniforms guard the roadway. They raise their rifles, halting the wagon. “State your business at Camp Nelson.”

Jackson pulls a letter from his pocket. “Mister Winston Giles of Woodville Farm in Woodford County, Kentucky, has sent provisions to his former employee, Isaac Alexander, who enlisted in Lexington.” He nods at me. “This is Isaac’s son, who’s visiting his father for the day.”

The soldiers don’t even glance at the letter. “No coloreds allowed unless they’re enlisting. Be on your way.”

“I believe we’ll be allowed.” Jackson thrusts out the letter. “This letter is a pass, signed by Brigadier General Speed S. Fry.”

The two soldiers read the pass, and then they study us like they don’t know what to make of it.

“All right then.” One soldier hands back the paper. “But take care of your business and leave. Colored recruits are bunking in the Soldiers’ Home on your right.”

“Thank you, officers.” Jackson clucks to the mules, and our wagon lurches ahead.

When we’re out of earshot, I whisper, “Who is Brigadier General Speed S. Fry? And how’d Master Giles get a pass?”

“He’s the man in charge of the camp. Mister Giles made his acquaintance in Lexington and got him to write us this letter.” Jackson chuckles. “Seems the general enjoys a good horse race and hand of poker as much as Mister Giles.”

The wagon passes through a wide gap in the fortifications. To the right, I see several cannons and rifle-pits. Soldiers pace back and forth in the hot sun, manning the defensive walls.

To the left is a fancy two-story white house with columns, porches, and three chimneys. “Bet that General Fry lives there,” I say.

My head swivels as we continue down the pike. All along the road are buildings: warehouses, barracks, hay sheds—even a bakery. Like Pa said in his letter: Camp Nelson’s a small town!

What I don’t see are any more soldiers. There’s nobody, black or white, drilling or marching. Instead, bare-chested black men are sawing and hammering boards, cutting and carrying logs, and unloading barrels and sacks. Their muscles gleam with sweat, and since they aren’t wearing uniforms, I gather they’re laborers, not soldiers.

“Place takes a lot of workers,” Jackson muses. Tugging the brim of his straw hat over his brows, he hunches his shoulders like he’s trying to hide.

“’Fraid some brigadier’s going to order you to dig his privy?” I tease.

With a grunt, Jackson hunches lower.

“The camp seems empty of soldiers. Must be they’re off fighting,” I guess. “Bet that’s where Pa is. Think he’ll be back in time to see us?”

“If he ain’t, we’ll wait.”

Down the road ahead of us there’s another two-story white building, but this one’s shaped like a horseshoe. It’s got four doors and rows and rows of windows. In the middle of the horseshoe, a smattering of colored men sits around a fountain. Others wait on porches or hang around in doorways. Most are barefoot and wear threadbare clothes. A few white men in military uniforms walk among them, writing on notepads.

Jackson halts the mules. “Must be the Soldiers’ Home.”

“Reckon those men are new recruits?”

“I reckon. Stay here. I’m going to ask about your pa.”

I watch Jackson approach several men who shake their heads. Then one of the soldiers gestures around back.

Jackson climbs into the wagon.

“Well?”

“Private Alexander is in the stables. The officer says we can take the mules there for the night.”

My eyes dance. “Pa’s a private! Bet he’s in the cavalry. Bet he’s grooming his mount, getting ready to ride out to war.”

Jackson laughs as he slaps the reins on the mule’s backs. “Bet one boy’s mighty excited to see his pa.”

The mules must smell hay and water because they trot up the hill to the stable. It’s painted white like the Soldiers’ Home, and it’s so long I can’t even see the far end. “Place must hold a hundred horses,” Jackson says.

When the wagon crests the hill, I count four stables, arranged like the sides of a box. The stables flank fenced enclosures filled with horses and mules.

“Have you ever seen so many horses and mules in your life?” I ask.

“There are quite a many.” Jackson halts the wagon at the end of the first stable. An open doorway leads inside. “Your pa could be anywhere. Hunt for him while I unhitch our mules.”

I jump from the wagon seat. My legs are stiff from riding so long, and for a minute, I hobble like an old man. Then desire to see Pa spurs me faster. I jog up and down the dirt aisle, peering into stalls. I ask everyone I see where I can find Private Alexander. Finally, a toothless colored man points to an end stall. A wheelbarrow stands outside the open door.

Grinning from ear to ear, I race down the aisle and swing around the barrow and into the stall. Pa’s forking up wet straw and manure.

When he sees me, astonishment spreads over his face. “Gabriel!” He drops the pitchfork and I jump into his arms. “What are you doing here?” he asks as he sets me down.

“Jackson and me came to visit. We brought you some clothes and supplies from Master Giles and Ma. Oh, Pa, so much has happened since you left!” In a rush of words, I tell him all about Jackson going to Saratoga, Newcastle beating Aristo, and Master sending us off for two days.

Pa looks grave when I finish. “I’m sorry my leaving caused so many problems. How’s your ma?”

“She’s missing you but glad to be free. Only she’s working jest as hard. Harder even.” I glance at the pitchfork and wheelbarrow. “Like you, Pa. How come you’re cleaning stalls? Ain’t you in the cavalry? Ain’t you fighting for freedom?”

Pa shakes his head. He’s leaner than when I last saw him, and the worry line in his forehead is deeper. “Not exactly, Gabriel. Come on, I’m ’bout done here.” He sticks the pitchfork in the manure he’s piled high in the wheelbarrow. “Let’s find Jackson. I’ll show him where to stable the mules for the night.”

I walk beside him, still chattering, as he pushes the wheelbarrow. “Why ain’t you off fighting? Where are all the soldiers? Why ain’t you in uniform? Where’s your warhorse?”

“Slow down, boy. Let me finish my work, and I’ll explain.” He dumps the load on a mound outside the barn, then pushes the wheelbarrow to a supply stall.

I’m busting to hear about camp life.

Finally he begins talking as we walk down the aisle. “Camp Nelson supplies food and horses to the soldiers who are already fighting. The ho

rses stabled in this barn are broken-down remounts. My job’s to get them fit for service again.”

“You mean you’re not a soldier?”

“I am a soldier, but even soldiers have work duties. I was lucky to be assigned to the stables. I could be digging ditches or building walls like most of the colored recruits.”

“You mean until you fight, right?”

“Right. Although when I first arrived, we almost had a run-in with John Hunt Morgan.” Pa’s eyes twinkle.

I suck in my breath. “The Rebel leader?”

“Yup. Seems he escaped from prison. All the colored recruits were given rifles and sent to Fort Nelson or Fort Jackson to defend the camp.” Pa chuckles. “Mind you, none of us had drilled with a rifle so it’s a wonder we didn’t shoot off our feet. It’s good Morgan and his band never showed.”

“That’s only ’cause you scared them away.”

“I doubt that. But since then the colored soldiers have been laborers. A war takes a lot of work and supplies, Gabriel.”

He must see the disappointment in my face, because he quickly adds, “Things ’bout to change, though. A colonel named Sedgwick was appointed to organize the colored troops. Why, black men pour into camp every day to enlist, mostly slaves hoping to find freedom. It’s a wonderful thing to behold.”

I nod, remembering Corporal Blue and Company H. “Soon you’ll be fighting Rebels, too,” I tell him.

We leave the barn and find Jackson by the wagon. The two men slap each other’s backs. We show Pa the supplies Ma sent and then bed down the mules. A white soldier with stripes on his uniform dismisses Pa and the other stable hands, and we file to the mess hall.

My stomach’s rumbling with hunger, and I stand in line with the others. I take a tin plate and hold it out to a man who serves up potatoes, gravy, and greasy pork, then I follow Pa to a long plank table. I slide next to him on a rough-hewn bench. Jackson sits across from us. We’re elbow to elbow with soldiers.

“This mess hall needs Cook Nancy,” I say as I fight to cut the gristly pork. “Be thankful we got vittles,” Pa says. “Before Colonel Sedgwick came, food for colored recruits was sparse. And if it wasn’t for Mr. Butler of the Sanitary Commission, we’d be eating boot leather and sleeping under the stars.”

“Why don’t they treat you better?” Jackson asks. He points his fork at the men around the table. “These are fine-looking soldiers.”

“Many of the white soldiers don’t want negroes in Camp Nelson,” Pa explains.

Jackson snorts. “You’d think the Yankees would want any able-bodied man that could hold a rifle or a shovel.”

“They do. Runaway slaves are coming in droves to the camp. Even though it can be risky.” Pa nods toward a burly black man shoveling food into his mouth. “Thomas over there ran off from a farm in Jessamine County. His master was so furious that he beat Thomas’s wife and children, then turned them off the farm to fend for themselves. Every day, I hear hard-life stories like that.”

Hard life reminds Jackson of the letters, and he pulls them from his vest pocket. “There’s a whole passel of women and children waiting outside the gates,” he tells Pa. “They asked us to take news to their men.”

Pa takes the letters and shuffles through them. “For a while the army let the families into the camp. They lived in shanties and tents by the commissary warehouse. But there got to be too many. The guards were ordered to raze the shanties and escort the families beyond the picket lines. Now orders say everyone who ain’t a recruit gets thrown out of camp. That includes women and children.”

Holding up the letters, Pa stands and starts calling out names. The soldiers eagerly come over to our table to hear the news we have to share about their wives and babies. Since most can’t read, they tuck any letters into their pockets. “Take them to Reverend Fee,” Pa says. “He’ll read them to you.”

When we finish eating, men up and down the benches swap tales of running off and enlisting as they pick food from their teeth with sharpened twigs. I drink in their stories, until slowly my eyelids droop.

Pa puts his arm around my shoulders. Leaning against him, I breathe in the comforting smell of horses, and soon the drone of voices lulls me to sleep.

***

Crack, crack, crack! Shots wake me.

I bolt upright, blinking in the dark.

The gray light of dawn is creeping through the glass panes of a lone window. I’m in a narrow bunk squeezed against the wall. Pa’s beside me, and I remember I’m at Camp Nelson.

Crack, crack!

Rifle shots! They can only mean one thing!

“Pa.” Furiously, I shake his shoulder, trying to roust him. “Wake up. Muster the men. Camp Nelson’s under attack!”

Chapter Ten

Crack! Crack! Crack! The shots come faster. Throwing back the blanket, I scramble over Pa and out of bed, stepping on someone’s arm. The room is piled with men sleeping two to a bunk and in blanket-wrapped rows on the floor.

“Hurry. We gotta find Jackson,” I tell Pa as I frantically hunt for my britches, which he must have pulled off before putting me to bed.

With a groan, Pa rolls over and throws his arm over his eyes. “Hush, Gabriel, before you wake the others. We ain’t being attacked. Those are Yankee rifles ringing in the Fourth of July.”

“What’re you talking about?” Kneeling on the floor, I search under the bunk.

“Independence Day.”

I know little of Independence Day. Since Master Giles is British, we don’t celebrate on the farm.

Sitting up, Pa glances down at me and chuckles. “Boy, how you expecting to fight Rebels with no britches?”

I flush mightily, embarrassed by my nakedness and stupidity. Still chuckling, Pa pulls my britches and a small haversack from under his pillow. “I believe this is what you’re hunting for.” He tosses the pants to me. “Let’s get washed up.”

By now, the men are stirring, and the bunkroom is pungent with the smell of dirty bodies. Tying my waist rope, I hurry after Pa. He’s buttoning the coat of his uniform as he heads down a hallway to the washroom where a pump brings water into an indoor sink.

“Master Giles needs one of these things.” I move the handle up and down. “Sure save a lot of bucket-carrying from the well.” I bend and peer at the water pouring from the spout. “Where’s it coming from?”

Pa splashes his face. “Long pipes run all the way to the Kentucky River.”

I splash water on my face, too, then scrub myself with a rag and small chunk of soap. The rinse water dripping into the sink is gray with yesterday’s dirt. “So where’d Jackson sleep?”

“In the wagon bed. He said there were too many men bunked in one room for his liking. He’ll have the team hitched and ready to go after breakfast.”

I stop scrubbing. “Go? We just got here.”

Pa dries his face with a rag. “That pass signed by General Fry only allows you one day in camp.”

“But I ain’t ready to leave,” I protest. “If I enlist, can I stay with you?”

“You can’t enlist, Gabriel. You can’t stay,” he says flatly. Tossing me the rag, he hurries from the washroom.

“But, Pa!” Hastily I dry my face, tears pricking my eyes at the thought of leaving him. A bear of a man pushes past, knocking me against the wall. I hang the rag on a peg and slither past him and into the hall. It’s teeming with black men of all sizes. A few are about my height, so I know I can pass for older. I’ll enlist today, and Pa can’t deny me!

In the bunkroom, Pa’s tidying up around his bed.

“I want to stay with you,” I say, trying to keep my voice from cracking.

Pa folds the blanket. “I don’t want you to leave, either. I miss you with all my heart. But these are hard times, Gabriel. We all have to do what’s best.” He looks down at me. “And what’s best for you is staying on the farm—no matter how much you hate Newcastle—and caring for your ma. Besides, you’d have to lie to pass for older. That’s no way to sta

rt army life.”

I raise my eyes to his. Pa’s brows are pulled into a frown, so I know he ain’t going to change his mind. “Yes sir,” I say reluctantly.

A bugle blares from below.

“Time to eat,” Pa says. “Before you leave, I’ll show you and Jackson ’round the stable.”

Shoulders slumped, I follow Pa, the recruits, and the enlisted men to the mess hall, where we find Jackson holding out his plate for doughy griddlecakes. But there’s creamy butter and sweet molasses, and I fork down a stack despite my sadness at leaving Pa.

When we’re finished, Jackson and me go with Pa and his squad to the stables. A white corporal leads us up the hill. Once we’re at the stables, the workers receive their orders and break off. We follow Pa to the barn where I found him yesterday.

“We’re each assigned stalls of horses,” he explains to us. “I’ve got a sorry bunch from a cavalry regiment that fought in Tennessee. Soldiers rode them hard and fed them harder. The forage last winter was mighty poor, and many animals gave out.”

As soon as he starts talking about horses, Pa’s worry lines disappear. He opens a stall door. A handsome bay greets him, and Pa pats his neck fondly. “Horses have numbers, not names. Number eighteen here had saddle sores and hoof-rot. He’s ’bout healed.”

He opens the door to the second stall. “This is number fourteen. His injury is going to take more time.”

I go inside. A sorry-looking chestnut stares from the corner. Scars mark his withers and a wound oozes on his neck.

“Number fourteen was shot in battle. He was lucky to make it out alive.” Pa shakes his head sadly. “Like soldiers, horses are dying on the battlefield.”

“Only they didn’t choose to fight,” Jackson says. “And they sure didn’t get no enlistment fee.”

I scratch number fourteen under his mane. I never thought about horses dying in battle without any choice—or glory.

Pa’s kept the wound open so the sickness can drain out. “Did you tell the Yankees about your healing salves?” I ask him.

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

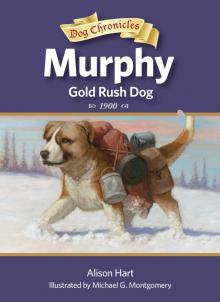

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog