- Home

- Alison Hart

Gabriel's Horses Page 6

Gabriel's Horses Read online

Page 6

He shrugs. “Then he’ll keep on whipping Aristo. And word is, he’ll be after you next.”

I bite my lip. There’s nothing more to say about it ’cause I can’t stand up to a mean white man. Not like those colored soldiers did. “What are you doing here now, Jackson? You could be at Major Wiley’s where you don’t have to mess with Newcastle.” I know I sound ornery, but I can’t help it.

“I got my reasons.” Jackson stands. “Look, your ma sent me to find you. She’s waitin’ for us in the summer kitchen. I believe she has a surprise. So dust off the hay and don’t disappoint her,” he says as he leaves.

A surprise? When Jackson’s footsteps grow faint, I pop my head from the hay and dry my dusty tears. Could it be a letter from Pa?

Scrambling to my feet, I wade through the hay and peek out the doorway. There’s no sign of Newcastle. I sprint from the barn and across the hay field, leaving a trail through the high grass. I weave around the fruit trees in the orchard and dash to the front of the Main House. Old Uncle’s in the yard pushing a grass mower. Master Giles had the newfangled machine sent from England, so his lawn would look as fancy as the Queen’s.

Vaulting the picket fence, I trot up to Old Uncle. He’s pushing the mower so slowly it appears like he’s walking in place. His hair is as white as Mistress’s linens, and his skin’s as parched as cured tobacco. He’s so old that he’s forgotten his age.

“Where you going in such a fired-up hurry?” he asks me. Stopping in the shade, he dabs his wrinkled brow with a rag.

“Anything faster than a turtle is ‘fired up’ to you, Uncle.” I nod toward the main house. “I’m headed to the summer kitchen. Ma’s got a surprise.”

“I’m comin’ with you.” He leans the mower handle against the tree trunk. “Dis hot work. ’Sides, I seen Annabelle picking blackberries in the garden.” He licks his lips and a twinkle lights his rheumy eyes. “You reckon a nice berry pie could be de surprise?”

“Might be.” Taking his arm, I help him up the walk. “Might be a letter from Pa.”

He hands me his rag. “Best wipe dose tear streaks off before you go into de kitchen. Don’t want your ma to see ’em.”

Hastily, I scrub my cheeks with my sleeve.

“Dat new trainer been beatin’ on you?” he asks, plucking a wisp of hay from my hair. “If so, hide in my cabin tonight, not dat hay mound. Ain’t nobody find you in my cabin.”

“No sir. He’s beatin’ on my horse.”

Old Uncle grunts in disgust. “A man dat beats one of God’s critters ain’t a man. He’s a coward.”

“Then the world’s full of cowards.”

“Dat don’t mean you have to be a coward,” he says.

We reach the marble stairs that lead to the portico, and I steer Uncle down the brick path to the back of the house. His steps are labored, but his voice is defiant. “Only cowards beat those that are more helpless. I’ve lived my life respectin’ the Lord’s creations, and when I die, I’ll join Him in heaven,” he says with conviction. “But dat wicked ol’ coward Newcastle, why, he ain’t never goin’ to see the light of heaven.”

“That don’t help ’Risto now,” I grumble.

“Den you gotta help ’Risto.”

I roll my eyes. Old Uncle sounds like Jackson. Don’t they know I’d help that poor horse if I could? It was all I could do to keep from leaping on Newcastle and bashing his head in. Only Pa taught me never to lay a hand on man or beast. What am I supposed to do?

Voices come from the open door of the summer kitchen, a small, slat board building behind the Main House. I haven’t seen Annabelle since I been back from Lexington, but I know she’s heard all about my winning the race. So when Old Uncle shuffles into the kitchen, I follow with a swagger.

The room’s fire-hot and smells like fresh bread. Ma and Annabelle are pounding dough. Cook Nancy’s pulling a warm loaf from the brick oven. Jackson’s in the middle, sitting court, his legs stretched out in front of him.

“Why, we jest in time.” Old Uncle sniffs the air. “Smells like Christmas in here.”

Annabelle gives me a sour look. Flour covers her cheeks, chin, and hair. “Did a strutting rooster follow you in here, Old Uncle, or is that Gabriel behind you?” she asks.

“It’s Gabriel, all right, the fine jockey,” I brag.

“You two quit sassing each other and listen to this,” Ma says. Wiping her hands on her apron, she pulls an envelope from her pocket.

I was right. It is a letter from Pa!

I pull up a chair for Old Uncle and then perch on a stool. Annabelle and Cook Nancy sit at the table with Jackson. Ma stands in the center of the kitchen, clears her throat, and reads, “Dear Lucy and Gabriel, I miss you with all my being.” Looking up, she grins as wide as a new moon.

I grin, too. “Ma, when did you learn to read?”

“Annabelle’s been teaching me.” Her cheeks redden under the splotches of flour. “’Sides, I’ve read that first part so many times I know it by heart. Come on, Annabelle.” She gestures for Annabelle to rise. “You finish readin’. The rest of the words are too hard.”

Annabelle takes the letter and begins again:

Dear Lucy and Gabriel,

I miss you with all my being. I’ve been at Camp Nelson for one week. It’s as big as a city, with a hospital, warehouses, a blacksmith shop, and a sawmill. The camp supplies goods for the Union armies fighting in the war. Wagons travel in and out daily. I’ve been mustered in and will soon begin training. Barracks are crowded but the food is plentiful.

I’ve met so many colored recruits that I’ve lost count. Most are as homesick as I. Reverend Fee has been most helpful in raising spirits and writing letters, including mine to you.

I hope all is well at Woodville. Every day I pray for you, my sweet Lucy. Keep your faith that we will soon meet. Gabriel, please forgive your father for leaving without a proper goodbye. Care for the horses as if I was there. God bless you all.

Your loving husband and father,

Isaac Alexander

“Oh my.” Ma has tears in her eyes and she blows her nose in her apron. Cook Nancy gives a wistful sigh, and even Annabelle’s eyes are misty.

The letter makes me miss Pa more than ever.

Old Uncle whaps the table with his palm. “Where dose blackberries you picked dis morning, Miss Annabelle?”

“Right here, Uncle.” Annabelle spoons the berries out into wooden bowls and pours a little cream over them, then hands us each a bowl. For a few moments, my only thoughts are of sweet berries.

When Jackson eats his fill, he clears his throat. “I have an announcement, too.”

I prick up my ears. Could it be news about Saturday’s race?

“I’m planning on leaving Kentucky,” he says. “Goin’ up North.”

“What?” I almost fall off my stool. “You’re leaving? Jackson, you can’t!”

“I don’t have a choice. Mister Giles got Flanagan riding for him. There ain’t enough other work at Major Wiley’s. It’s time to move on.”

“But Jackson,” I protest, “Woodville needs you. Flanagan can’t ride worth a flip.”

“It ain’t just that, Gabriel. Sometimes a man just knows when it’s time to go. ’Sides, I hear there’s a resort town in New York state where horses race almost daily, even during these war times.” Leaning forward in his chair, Jackson rests his elbows on his knees and goes on with his story. “A town called Saratoga, where the streets are lit with gas lamps and the hotels have five stories of rooms. All the famous jockeys like Abe Hawkins will be riding there.” He straightens. “Sounds like a place where a good jockey can make his fortune. I’ll leave in a couple of days.”

Suddenly, the berries taste as sour as Jackson’s news. I spit the last bite on the floor. “First Pa left. Now you!”

Jackson pokes at the blackberries in his bowl ’cause he can’t meet my eyes.

“Now, Gabriel.” Ma tries to put a comforting arm around my shoulder, but I push it away.

>

“Then take me with you, Jackson. I’m a good rider. I can make my fortune, too.”

“You’re too young, Gabriel. ’Sides, who’d care for your Ma? Who’d watch over the horses?”

I don’t have an answer. My lower lip trembles. I glance around the room. Jackson, Annabelle, Ma, Cook Nancy, Old Uncle—they’re all looking at me, sorrow in their eyes.

Furious, I jump off the stool. “Leave then, Jackson. Leave! ’Cause I don’t care!” I shout. I stomp out the door and race through the kitchen garden and into the orchard. The evening sun’s falling behind a cloud, casting a dusky gray light over the fields. I need another hiding place, this time to grieve. First Pa. Now Jackson. How can they just up and leave?

Head hanging, heart heavy, I aim for Old Uncle’s cabin in the slave quarters where no one will find me.

***

Old Uncle doesn’t say a word to me when he comes in. He settles into his bed, quilt pulled to his chin. When night falls, I slip from the cabin and close the door to his snores, which rattle the room like a gourd drum. It’s late, and the quarters are mostly quiet. A few field hands sit on their stoops, enjoying the warm night breeze, and pipe smoke drifts through the air.

I stop for a moment, listening to their urgent whispers. It seems that Newcastle wasn’t satisfied with beating Aristo. Now, whip in hand, he’s out hunting for me. Silent as a thieving raccoon, I sneak from the quarters carrying a stub of candle.

I’d be safer staying in Old Uncle’s Cabin, but I have to check on Aristo.

As I dart down the path, I jump at leaves rustling in the underbrush. Could be Newcastle crouched in the shadows cast by the moon. Could be the witch who leads men astray at night.

Heart thumping, I race across the hay field, palm cupping my candle flame. The training barn’s dark. Jase and Tandy sleep in the stalls, so I shield the light as I tiptoe down the aisle. Stretching tall, I peer over Aristo’s half door. The colt’s hiding in the corner.

I make a soft kissing noise. He flicks an ear. One hind hoof is cocked like he don’t want company. I hold the candle high, trying to see how bad Newcastle hurt him.

“’Risto, it’s me,” I whisper as I open the stall door. I blow out the candle, afraid of setting the straw on fire. There’s enough moonlight coming through the stall window to see the colt. When I step closer, he shies sideways.

“It’s me, horse,” I croon. Placing my palm on his neck, I scratch under his mane, then stroke him from withers to flank. He blows a happy sound, and his ears fall limp. But when I touch his chest, he shudders and moves away.

“I ain’t going to hurt you. I just want to see what Newcastle’s done.” My fingers lightly graze his chest muscles, and I feel thin, crusted-over scars where the lash must have fallen. Newcastle’s beat the horse between his front legs, hoping to hide the marks. Hate fills me. The man had no right!

A noise outside the stall makes me tense. Lantern light fills the barn, and heavy footsteps trod down the aisle. The hair prickles on the back of my neck.

Newcastle!

I swallow my fear. This time, I ain’t going to run from the trainer.

This time, I’ll take the lash instead of Aristo. I twine my fingers in the colt’s mane, and with my back toward the door and my legs trembling, I brace myself for the first stroke of the whip.

Chapter Nine

Light streams into the stall. Aristo startles and blinks. Squeezing shut my eyes, I sing quietly to the colt, “When we all meet in heaven, there is no parting there.”

“Gabriel?” Instead of a whip crack, I hear Master’s voice. “What are you doing in here at this late hour?”

I look over my shoulder. He’s standing in the doorway, the lantern raised. The golden light blinds me. Relief fills me, but then confusion muddles my thoughts.

If I tell Master about Newcastle, the trainer will hunt me for the rest of my days. If I don’t tell him, the horses will bear the brunt of the man’s meanness.

Then Aristo nuzzles my side, and I know what path I must take.

“It’s ’Risto, Master. Newcastle beat him.” Tugging on the colt’s mane, I pull him from the corner.

“Beat him?” Master sets the lantern on the floor. “Hold him still.” He approaches the colt, who eyes him warily as he bends to study the wounds.

Master straightens. He nods once, his face weary. “See to his care, Gabriel. I’ll leave the lantern.” He strides from the barn, his boots thudding down the dirt aisle.

“Lord forgive me, I’ve done it now.” I flatten my palm against Aristo’s neck. “When Newcastle finds out I told on him, the trainer will flog me raw,” I tell the colt. “But Pa told me in his letter to care for the horses, so I gather it’s my duty.”

Still, the threat of a beating sends a chill up my spine. I’ll have to spend my days staying clear of Newcastle.

Reaching around the doorway, I lift the halter and rope from the wooden peg. Pa always cared for the sick horses, and now Master’s putting his trust in my doctoring.

“Come on. Let’s get some of Pa’s healing salve on those cuts.” I slip on the halter and give Aristo’s ears a rub. He pushes me with his nose, but I can tell the whipping has stolen some of his fire.

“Salve will heal your wounds,” I promise him, but then I shake my head, knowing it will take more than salve to heal his spirit.

***

Early the next morning, Jackson shakes my shoulder. “Get up, boy. We’re going on a journey. Mister Giles thinks it’s best for you to be out of Newcastle’s way for a few days,” he says as he tosses my pants on the bed.

Yawning, I sit up. “A journey? Where? You taking me to Saratoga with you?”

“No, nothing like that. We’re going to see your pa. I promised, didn’t I?”

That snaps me awake. Tossing back the quilt, I jump from my bed and grab my pants.

When I hurry outside, shirt untucked, the team of mules is waiting in front of our cabin, already hitched. No one else is stirring yet, but Ma’s filling the wagon bed with baskets of food and gifts for Pa. She kisses me goodbye and waves as we set off for Camp Nelson.

The wagon creeps down the dusty road. Every once in a while, Jackson slaps the reins on the backs of the mules, trying to move them along. By midmorning, the sun’s so hot and the air’s so still, the smack of the reins has no effect. Those mules aren’t about to hurry.

I’m still mad at Jackson for leaving, but he is taking me to see Pa, so I share some of Ma’s biscuits with him.

“Reckon we’ll get to Camp Nelson before nightfall?” I ask, biting into one.

“I reckon we’ll get there for supper,” Jackson replies. He’s swaying lazily on the wagon seat, enjoying the biscuit. Like me, he’s wearing a straw hat to keep the sun off his face. “That is if we don’t get caught by Newcastle.” Slanting his eyes at me, he chuckles.

I scowl. “Ain’t funny. You’re leaving for some fancy resort when we get back to the farm, while I have to stay and face that man every day.” My anger spills out. “And one day, I’ll be coming ’round a corner, and there he’ll be, whip in his hand. What’ll I do then?”

“Turn tail and run like a fox,” Jackson says with a laugh.

“Easy for you to say,” I grumble.

We ride along, silent except for chewing. Every now and then a farm wagon passes us, but we’re not on a main road, so mostly we’re alone. Tipping my straw hat up off my forehead, I glance around.

I’m excited that we’re going to see Pa and glad to have fled Newcastle’s whip, but the trip doesn’t thrill me like the one to Lexington. We haven’t passed a single sweet shop or fancy hotel. Just miles and miles of hard-packed dirt road bordered by thick woods or poor farmland.

“At least One Arm ain’t lurking around these parts,” I tell Jackson. “There aren’t any railroad depots to burn or Thoroughbreds to steal.”

“One Arm ain’t foolish enough to travel this close to the Union soldiers at Camp Nelson, either,” Jackson says. “He d

on’t want no colored troops after him with their bayonets.”

I grin. “I bet Pa’s drilling right now. I can’t wait to see him in his uniform! He’ll look as splendid as Corporal Blue.”

Jackson gestures toward the wagon bed behind him. “Grab me one of your Ma’s sweet potato pies and that tin of water. I gotta eat something or I’ll fall asleep on this slow journey. A mule ain’t no racehorse, that’s for sure.”

Climbing into the back of the wagon, I rummage through the piles. Ma’s packed knitted socks and enough biscuits for a company of soldiers. I pass a sweet potato pie to Jackson, who digs into it with his fingers.

“Save some for me!” I say as I scramble back onto the seat.

Finally, the mules turn south onto the Lexington and Danville Turnpike, and the way gets busier. For the next few miles, canvas-covered supply wagons rattle past, and I guess we’re getting near Camp Nelson. My palms start sweating. Pa doesn’t know we’re coming, and I can’t wait to see the surprise on his face.

Up ahead, we spy several empty wagons parked alongside the road. Then we see a cluster of raggedy tents and log shanties. Around them, black women tend fires and wash clothes like they’ve set up house.

As we get closer, half-naked children appear as if from nowhere. They trot alongside the wagon, asking our names. Finally, Jackson halts the mules next to a light-colored woman hoeing a meager plot of earth. A few rows of corn poke through the dirt. A bare-bottomed youngun, clinging to the woman’s skirts, sways unsteadily with each thrust of his mother’s arms.

“Excuse me, ma’am. Is Camp Nelson far?” Jackson asks, all polite.

Stopping her hoeing, the woman leans on the handle. Sweat drips down her cheeks, which are hollow with hunger. I glance at the boy. His saucer-round eyes stare up from a pinched face, and I can count every rib in his skinny chest.

She thrusts her chin down the road. “Just ’round the corner. You boys enlistin’?”

“No ma’am. Visitin’.”

Sticking her hand in her apron pocket, she pulls out a wrinkled piece of paper. “Please then, will you take this to Alonzo Jenkins?” Desperation rises in her voice. “Tell him there ain’t no more food for his babies.”

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

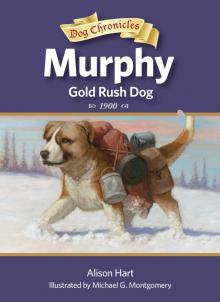

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog