- Home

- Alison Hart

Gabriel's Horses Page 8

Gabriel's Horses Read online

Page 8

Pa shakes his head. “Most of the Northerners I’ve talked to are city boys who don’t care beans about horses. They think they’re only for riding into battle or pulling cannons and wagons without mercy. At least the camp has a good veterinarian.”

“You know more than that veterinarian,” I brag. “Tell him ’bout your salves.”

Pa shrugs. “He don’t care. He’s got his own way of healing. But I have suggested some changes to Captain Waite. He’s one of the few cavalry officers interested in the horses’ care. I told him we should turn out the remounts on cool nights so they can graze and keep them in during the heat of the day when the flies are pesky. He agreed, and since then they’ve recovered faster. I believe the captain’s a good man, but still I need to tread carefully. Most officers don’t want advice from a colored man.”

Jackson makes a noise in his throat. “Seems to me you should be captain of the stable, not some Yankee.”

“Might be that Colonel Sedgwick will make you a captain—right, Pa?” I ask. He doesn’t answer, and as we leave the barn, his face gets a tight look. My gut gets tight, too, ’cause it’s time to say goodbye.

We hitch the mules, and then Pa holds me close. “Say hi to your ma for me,” he whispers, his voice husky. “Watch over her and that new babe she’s carrying. And Gabriel, keep riding and caring for the horses.”

I nod, my own throat too clogged to reply.

Moments later, Jackson whistles and slaps at the mules, and the wagon rattles down the hill toward the pike. I wave to Pa until he’s a blue speck. My heart aches, but I don’t want to cry in front of Jackson.

Our wagon bed is filled with packages, notes, and coins to give to the families outside the camp. When we pass a sutler’s wagon, Jackson halts the mules. Using his own money, he buys overpriced tins of potted meat, cans of Borden’s condensed milk, and a dozen molasses cookies. Then we drive out Camp Nelson’s gates, passing the guards along the picket line. Jackson salutes them, but they stare straight ahead, their backs as straight as fence posts.

As the wagon heads from camp, Jackson whistles. “Lookee there, Gabriel.”

A hundred or so black men are walking toward us down the road. They’re wearing tattered clothes and carrying bundles.

“They must be recruits,” I tell him. “Pa says more are coming into camp every day.”

Jackson halts the wagon, and the men pass us by. They nod tiredly, and we wish them luck.

Suddenly a carriage pulled by a team of horses barrels down the road. Careening wildly, it flies around our wagon and the black men before rattling to a stop across the road, forming a barricade into Camp Nelson. Instantly the black men bunch together, and the guards run from their posts.

Jackson and I watch, wondering what will happen next.

The driver jumps from his seat, opens the carriage door, and helps out an elderly white woman dressed all fancy. “Stop those colored men!” she screeches. Her gloved finger points accusingly at the black men huddled in the road before her.

“Stop them this instant!” she repeats. One hand holding a parasol, the other lifting her hooped skirt, she hurries toward the guards. “I am Missus Francine Templar from Boyle County, and those two men wearing straw hats are my able-bodied slaves. They have run away from my farm and I want them returned!”

“Uh, missus, uh . . . we don’t have the . . .” Flustered, the guards stammer uncertainly until a small squad of mounted soldiers trots from the camp.

“Good day, ma’am.” One of the horsemen nods to the woman. “I am Lieutenant Kline. I have orders from the post commandant to escort these recruits into Camp Nelson.”

“That’s fine, but I demand that you leave me my slaves. Those two, Lou and Jake. I need them to bring in the harvest and plant winter wheat.” She jabs her finger in their direction. “Lou, Jake! I order you into this carriage!”

“Ma’am. Please, quiet,” the lieutenant commands. Turning in the saddle, he addresses the band of recruits. “Your master or mistress’s consent is not necessary for your enlistment. No one has authority to order you back to the farm. Is there a man here who desires to remain a slave?”

Black heads bob and shake, and murmuring rises from the group. “No!” they finally reply in one strong voice, weary no longer.

Furious, Missus Templar stamps one foot. The mounted soldiers rein their horses around the slaves. With the guards leading the way, the recruits march past the carriage and the enraged Missus Templar and through the gates of Camp Nelson.

“Look at that, Jackson.” I nudge him. “We just saw freedom. And Pa’s right: It is a wonderful thing to behold.”

Buoyed by the sight, Jackson and me continue on our journey, stopping to hand out the goods to the families living roadside. Even though I’m sad about leaving Pa, my spirits stay high for several miles afterward. Just like on the trip to Lexington, I’ve seen and learned so many new things. Must be what Ma calls “growing up.”

“As soon as I can, I’m enlisting,” I tell Jackson. “Then I’ll be free, too.”

He grunts. “Boy, didn’t you learn nothin’ at Camp Nelson? A black soldier ain’t free.”

“That ain’t true,” I protest.

“Then why is your pa cleaning stalls for white soldiers’ horses?”

“All soldiers have duties,” I say, repeating Pa’s words. “Pa says Colonel Sedgwick is organizing colored troops. I bet next time we see Pa, he’ll be wearing a uniform with stripes on his shoulder. Already, he fought against Morgan. You watch, in no time he’ll be marching to Tennessee to fight Rebels.”

Jackson shakes his head. “That’s foolish thinking, Gabriel, but believe what you want.”

Angry at Jackson for doubting Pa, I retort, “You’re just against being a soldier ’cause you’re too cowardly to enlist.”

Jackson tips his head sideways and studies me. I bite my lip, sorry for my words. Jackson ain’t a coward. But I can’t have him speaking against Pa.

“Way I see it, most Yankees don’t care if black folks are free. That ain’t why they fighting this war,” Jackson says solemnly, like he’s thought on it awhile. “But you’re right, I am a coward. I don’t want to kill or die for freedom. That’s why I’m leaving for Saratoga tomorrow—to find freedom my own way.”

Crossing my arms against my chest, I turn away. I don’t want Jackson to see the tears I suddenly can’t hold back.

“I’m sorry I’m leaving you, Gabriel,” Jackson adds with a sigh. “And I’m sorry your pa left. But sometimes, ‘sorry’ ain’t enough to stop a man from what he needs to do.”

Chapter Eleven

The next day Jackson is to catch the train to Saratoga, New York. Renny will drive him in the carriage to the Midway depot. Before they head off, I hide in the weeds by the river where no one will find me.

Leaving Pa was hard, but at least he’s in Kentucky so I reckon I’ll visit him again soon. But Jackson? I ain’t never going to see my friend again. Now I know how Pa felt when he snuck off to enlist. Like him, I just ain’t brave enough to say goodbye.

When the sun gets hot and the mosquitoes pesky, and I reckon Jackson and Renny are long gone, I climb from my hiding place along the riverbed. In the distance, I spot one of Master Giles’s armed guards sitting under a tree by the bridge across the river. Since the scare with One Arm, someone patrols the pike around the clock. This sentry is sleeping, his rifle across his lap, his hat tucked over his face to keep off the flies.

I walk alongside a field of corn, colorful with field slaves plucking corn worms from the leaves. Their fingers are swollen from the stings. Their bare arms are scratched from the leaves. The sun beats on their heads, and sweat streams down their necks.

Since the war started, Master’s lost many slaves. Some died from the fever. Some ran north. Some ran to enlist. Some just ran.

Master’s always spouting off against slavery, yet he still owns slaves. He has so many, I don’t know a lot of their names. As I walk past the pickers, they stare at me, probably wond

ering why a strong boy like me ain’t working. If they were to ask, I’d tell them I haven’t worked since I got home from Camp Nelson. I’d say that I don’t care if I’m caught and whipped. Newcastle’s going to whip me no matter.

Mister Yancy, the colored driver, sits in the shade of a tree, fanning himself with a wide leaf. There’s a bucket of water and a dipper beside him.

“Mornin’, Gabriel. Drink?” he asks.

“No sir, but I ’spect those workers are thirsty.” I nod in the direction of the corn.

“I ’spect you’re right,” he replies, only he doesn’t move to offer them any.

I continue on, not sure where I’m going. I do know where I’m not going. I’m not going near Newcastle or the stable even though I’m lousy with missing the horses. I know, like Pa said, that I need to care for them, but my fear of Newcastle keeps me away.

Sweet singing floats from the orchard and stops my journey. I search the grove, spotting Annabelle up in a peach tree. Her bare toes cling to a lower branch while she reaches over her head for early peaches. Her straw hat’s hanging from a leafy twig; a basket is propped in the crotch of three branches.

I can’t resist. I tiptoe through the grass. When I’m right beside her, I yell, “Boo!”

“Aiiieee!” Annabelle screams. She sways and starts to fall.

Grabbing her around the knees, I hold tight until she regains her balance. Her skirt bunches up, and when I let go, she reaches down and slaps me soundly.

“Gabriel Alexander, how dare you peek up my dress!” she shrieks.

“I wasn’t peeking up your stupid dress! I was trying to keep you from busting open your pig head. Next time I’ll let you fall.”

“Next time don’t sneak up on me!” For a second, she glowers down at me, and then her expression softens. She pats at her skirt, making sure it ain’t hitched up. “Well, then, sorry I slapped you. I thought you weren’t being a gentleman.”

“Oh, like you such a lady.” I rub my cheek.

“It was just a tiny slap. Couldn’t have hurt that much.”

“It like to’ve knocked my ear off,” I grumble, and we both start giggling.

Annabelle passes me the basket and climbs from the tree so slowly and daintily, I have time to select a ripe peach from her basket. I take a big bite, letting the juice run down my chin.

“You could have asked permission,” she says, snatching the basket from my hand. “These peaches aren’t for slave boys. They’re for making peach pies for Master and Mistress.”

I snort and swallow the sweet flesh of the fruit. “Why don’t you tell them to pick their own peaches?”

Her mouth falls open.

“Then tell them to make their own pies,” I add. “I bet Mistress don’t even know how to hold a rolling pin.”

“Gabriel Alexander, what sassy remarks. What’s gotten into you?”

“Nothin’.” I toss my pit into the weeds. I wipe the juice off my chin with the back of my hand.

“Did your trip to Camp Nelson make you too bigheaded to live here anymore?” Annabelle sets down the basket and pulls her hat from the branch.

“No. But it did teach me something about freedom.” I pick up the basket. “Best let me carry that for you.”

Again she stares at me. “You might be bigheaded, but I do believe you learned some manners on your trip.”

“Naw. But my trip did show me something of the world. There’s a whole lot of life beyond Woodville.”

She tips her head forward and puts on her hat. “Like what?” she asks.

As we walk through the orchard, I tell her about Camp Nelson, the slaves marching to enlist, and the women outside the camp who’ve run away to be near their husbands. “Pa says the slaves are enlisting to find freedom.”

“Sounds to me like the men who enlisted left their women and children to starve,” Annabelle says.

“You sound like Jackson,” I tell her. “He scoffs, saying that black men who enlist work just as hard as slaves. ‘Freedom’s in Saratoga,’ Jackson says.”

Thoughts of Jackson riding far away on the train make my stomach turn sour again.

“A fine jockey like him will find freedom in the North,” Annabelle points out.

“Perhaps,” I mutter, adding, “Ma says I’ll find it here at Woodville Farm with Master’s horses. She says if I keep riding, I can save my earnings and buy my freedom.” I sigh heavily. “Only now that Flanagan’s here, no chance I’ll be Woodville’s jockey.” Angrily, I grab another peach. Before I can bite into it, Annabelle plucks it from my fingers and plops it back into the basket.

“Seems everybody has a different idea of freedom,” she says. “If you asked me what freedom is, I’d say ‘reading and writing’.” Stopping by the gate in the kitchen garden, she turns to face me. “What do you think freedom is, Gabriel?”

I shrug, puzzled. No one’s ever asked me that question. “I don’t know.” From an upstairs window of the Main House, I hear the tinkle of Mistress’s bell, beckoning Ma.

Frowning, I kick open the gate. “I do know what freedom ain’t,” I declare as I stride down the brick walkway. “It ain’t running up and down the stairs fetching and carrying for Mistress. Ma is supposed to be free, but she’s still actin’ like a slave.”

Annabelle darts in front me. “Gabriel Alexander, I’d like to slap you again. Don’t you ever disrespect your ma. She’s the finest, kindest woman I know.”

Reaching out, she yanks the basket from my grasp and sets it on the ground. Then she takes my hand and drags me down the walkway toward the Main House.

Annabelle’s taller than me, and plenty strong. And she’s so riled up there’s no telling what she has in her mind to do.

“Where you taking me?” I ask.

“To show you why your ma is fetching and carrying.” She pulls me into the Main House and down the hall to the slave stairway. Grabbing the side of the doorjamb, I brace myself with my free hand. “Oh, no. No, Annabelle. I ain’t going upstairs.”

“Yes, you are.” Annabelle yanks my hand so hard my skin burns. “Or I’ll tell your ma you were hiding by the river this morning, not cleaning tack in the barn like you said.”

I grimace. Ma hates liars even more than gamblers and shirkers.

Letting go, I reluctantly follow Annabelle up the narrow stairs. When we reach the second floor, Annabelle puts a finger to her lips and leads me down the hall to an open doorway. She peeks into the room, then gestures for me to look, too.

Whatever it is, I don’t want to see.

Annabelle aims her mad eyes at me, and I peer into Mistress Jane’s bedroom. A four-poster canopy bed sits in the middle of the polished wood floor. Mosquito netting is draped from the bedposts, but I can see Mistress Jane through the gauzy material—least I think it’s Mistress Jane. The person in the bed’s so tiny, she scarcely wrinkles the sheets.

“Go on in,” Annabelle whispers, giving me a push.

I stumble through the doorway. Mistress Jane’s head is turned away. Her arm lying on the sheet is withered and pale. A bell sits beside her curled fingers.

“I didn’t know she was so sickly,” I whisper to Annabelle.

“She’s going to die, Gabriel. She’s rich and free, yet she’s going to die anyway. That’s why your ma still fetches and carries.” Annabelle’s voice trembles. Tears pool in her eyes as she gazes at Mistress Jane. “Not ’cause your ma’s still a slave. ’Cause Mistress Jane needs her and because your mama has a soul.”

I swallow hard, my gaze frozen on Mistress Jane, and I remember all the times Ma’s been called to the slave quarters to tend the sick or deliver babies.

Annabelle blinks, and the tears trickle down her cheeks. “So if you asked your ma about freedom, she’d say it ain’t just about leaving. It’s about staying and caring for others, too.”

Mistress Jane moans and I jump. Mumbling something foolish, I back out of the room, leaving Annabelle behind to grieve for her mistress.

By the tim

e I run from the Main House, freedom’s making my temples throb. Or could it be Annabelle’s slap?

Old Uncle’s in the kitchen garden hoeing a row of potatoes. When he spies me, he waves for me to stop. “Dat Newcastle still beatin’ on your horses?” he asks.

“They ain’t my horses, Uncle,” I snap.

“You care for ’em, don’t you? You luv ’em, right? Den dey your horses.” He answers his own question with a satisfied nod and returns to his hoeing.

I kick the soft earth with my foot. I’m ashamed to tell Uncle I haven’t seen Aristo and the other horses for three days. Though why should I worry about what an old man thinks? And why should I worry about what Ma, Pa, Annabelle, or Jackson thinks? Let them think what they want about freedom. I ain’t doing what they want me to do. I ain’t fetching or carrying or taking a whip for any man.

I’m going through the garden gate when Tandy comes flying down the lane from the barn, his arms flapping like a crow’s wings. “Gabriel!” he calls as he runs, his words coming in gasps, “Newcastle’s . . . going . . . to . . . Aristo . . .

I jog toward Tandy, meeting him halfway. Holding his stomach, he leans over and gulps air.

“Slow down and talk right, Tandy. What’s this about Newcastle?”

“Newcastle’s tryin’ to saddle Aristo. Only Aristo’s rearin’ and fightin’. Newcastle tied him up and went to get his whip.”

The blood rushes from my face.

“He’s mad enough to kill that ornery colt. You gotta do somethin’, Gabriel!”

“Me?”

“Your pa’s gone. Jackson’s gone. Cato, Oliver—ain’t nobody wants to tangle with Newcastle.”

“Where’s Master Giles?”

“I don’t know. Hurry, Gabriel.” Turning toward the barn, he starts off like he expects me to follow.

Only I can’t move.

My feet feel like they’re nailed to the earth. Aristo ain’t your horse, I tell myself. This ain’t your fight.

“Gabriel, come on!”

I clench my fists. I picture Aristo hiding in the corner of his stall, his skin torn after Newcastle’s whipping, and a howl rises uncontrollably in my chest. Maybe I ain’t like Pa or Ma. And maybe I am a coward, but I can’t let Newcastle beat Aristo any more.

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

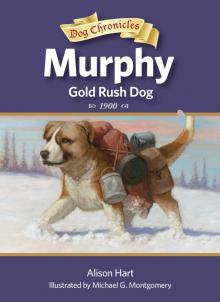

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog