- Home

- Alison Hart

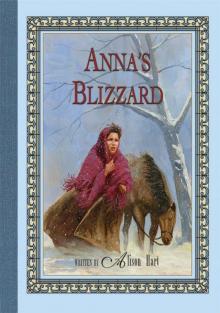

Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Read online

Published by

PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS

1700 Chattahoochee Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112

www.peachtree-online.com

Text © 2005 by Alison Hart

Illustrations © 2005 by Paul Bachem

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Cover design by Loraine Joyner

Book design by Melanie McMahon Ives

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hart, Alison.

Anna’s blizzard / by Alison Hart.– 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Having never excelled at schoolwork, twelve-year-old Anna discovers that she may know a few things about survival when the 1888 Children’s Blizzard traps her and her classmates in their Nebraska schoolhouse.

Includes bibilographical references

ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-927-8 (ebook)

[1. Survival–Fiction. 2. Blizzards–Fiction. 3. Schools–Fiction. 4. Nebraska–History–19th century–Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.H256272Ar 2005

[Fic]–dc22

2005010825

ANNA’S BLIZZARD

WRITTEN BY Alison Hart

To

brave

girls

everywhere

—A. H.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

More About Life on the Prairie in the 1880s

CHAPTER ONE

Nebraska—January 12, 1888

Get along now, sheep.” Leaning down from her pony Top Hat, Anna Vail swatted a woolly back with a coil of rope. The sheep trotted on spindly legs toward the gate leading into the pasture. Their small hooves tapped the frozen sod. Their bleats filled the crisp air.

Suddenly, a shadow swooped across a white patch of snow.

Anna glanced up. Hawk! Her gloved fingers tensed on the reins as the startled flock surged away from the gate. Top Hat darted after them, throwing Anna onto his rump. She grabbed a hunk of mane as he swung right, circling the small herd. The sheep flowed left like a puddle of spilled milk. When they threatened to miss the gate opening, Top pinned his ears and nipped them through.

Anna pushed the gate closed behind the retreating sheep. As she secured it with the coil of rope, she blew a frosty breath.

“You almost unseated me chasing those silly critters, Top.” She patted the pony’s neck. “Now we best hurry home or Mama will have a fit.”

Top broke into a jog, jostling Anna on his bare back. She tightened her legs against the pony’s sides, fuzzy with winter hair. Her calf-length skirt hiked up around her knees. She wore a jacket and the wool stockings, cap, scarf, and wristlets that Mama had knitted. All were itchy. All smelled like sheep, but they kept her warm.

Top trotted quickly through a snowdrift left over from the last storm. For the past two days it had been unusually warm, and prairie grass poked through the melting snow.

It’s almost like spring’s arrived, Anna thought. But she knew better. Nebraska winters often lingered through April. She’d even heard tales of frost in July.

Top’s gait quickened when he spotted the windmill and the barn that meant home. Minutes later, Anna spied Mama, a speck in the front of the sod house. She was waving in Anna’s direction.

“Uh oh. Mama’s on the lookout. She’ll blister my backside if I’m late again for school,” Anna told Top. Slackening the rein, she urged the pony into a canter.

Every morning after a breakfast of cornmeal mush, Anna and Top cared for the sheep. In spring, summer, and fall, they followed the herd as the sheep grazed on the unfenced land. But in winter they had to go to school.

“I’d rather be herding sheep, Papa,” Anna had protested.

But Mama had insisted. “Anna’s eleven years old now,” she’d told Papa. “This winter she needs to spend more time with scholars and less time with critters.”

Mama just didn’t understand. Sheep didn’t giggle when Anna misspelled “state” or stumbled over addition facts.

Flicking his ears, Top cantered past the sheep shed and pen. Anna reined him around a patch of prairie dog holes. Then she aimed the pony toward the fire ditch that circled the house and barn.

She whooped as Top leaped the ditch and careened into the yard of the sod house. Mama was backing out the front door, tugging a ticking-striped mattress. Anna’s four-year-old brother, Little Seth, was in the doorway pushing at the other end.

Top threw up his head at the sight and skidded to a halt. Anna shot over his neck, landing heels over head in the flock of chickens, which squawked and flapped in all directions.

Jumping to her feet, she hooted, “Hoowee. That was some dismount!”

“Anna Vail, that is no way for a lady to conduct herself,” Mama scolded as she and Seth leaned the mattress against the outside wall of the soddy.

Turning, Mama propped her fists on her hips. The frayed hem of her long skirt swept the ground. A woolen shawl hung from her shoulders and a scarf peeked from under her bonnet.

“Oh, don’t worry, Mama,” Anna said. “That little tumble didn’t hurt a bit.”

“I’m speaking of your school dress and jacket. Covered with prairie dirt. Just like everything else in this godforsaken land.” Mama, born and bred in Virginia, pined for green grass, tall oaks, and rolling mountains.

Anna hurriedly brushed off her skirt.

“Now get a move on, young lady,” Mama continued to scold. “I’ll not have Miss Simmons calling on me again to complain of your tardiness.”

“Yes ma’am.” As Anna hurried into the house, she flung her long braid over one shoulder and righted her knit cap.

The Vails’ soddy consisted of two rooms. A small family bedroom took up the back of the house. In the front room, where they spent most of their time, there was a glass-pane window, a luxury on the prairie. Framed pictures and an oval mirror hung on the white-washed walls. A stove stood in the middle. Beside it was a basket of wood and two rocking chairs.

To the right of the stove were a kitchen table, cupboard, sink, and counter. Sacks of fried corn, dried beans, and onions hung in one corner. Shelves filled with canning jars and crocks lined the walls.

Anna grabbed her lunch pail, tablet, and slate off the kitchen table, then hurried back outside. Top stood stiff-legged, eyeing Little Seth, who was dragging a quilt across the yard. Little Seth was too young for school, so he stayed home to help with chores.

Anna wished mightily that she could stay home.

“Today would surely be a good day for cleaning the sheep shed,” she said to Mama as she slid the slate and tablet under her jacket.

“Might be, but you’re going to school.” Hands still on her hips, Mama closed her eyes and tilted her chin toward the morning sun. “Almost like spring’s in the air,” she murmured, the golden light softening the lines in her face. “It’s a shame it’ll never last.” She opened her eyes. “At least we have a good day to air the mattresses and pick lice.”

Anna perked up. Picking lice was a heap better than doing sums. “I can help!”

“No, missy, you will not. Little Seth and I will wrestle the vermin. You will triumph over grammar rules.”

Anna’s shoulders slumped. Mama was not giving way.

And she couldn’t look to Papa for sympathy either. He had left early that morning, heading into town during this break in the cold weather for much-needed supplies. Anna wished she’d hidden in the wagon bed and gone with him.

With a sigh, Anna looped the lunch pail handle over her arm. Grabbing Top’s mane, she vaulted onto the pony’s back.

“Goodbye, Little Seth,” she called.

“Bye, Anna Bandanna!” Twirling a rope over his head, her little brother took off after the chickens, as if trying to round them up.

Mama fixed a stern gaze on Anna. “No dallying this morning, and keep your cap snug over your ears. This weather is as deceiving as your father when he convinced me to move out West.”

“Yes ma’am,” Anna replied politely. But as soon as she trotted from Mama’s sight, she tore off her cap, shook out her long braid, and kicked Top into a canter. Mama might long for life far from the Nebraska plains, but not Anna. Like Papa, she loved the prairie whether it was bristling with summer heat or buried under winter snow.

In no time, Anna reached the Friesens’ house. The Friesens were their closest neighbors. Her friend John Jacob and his older sister Ida had already left for school. Mr. and Mrs. Friesen were in the front yard of their soddy, surrounded by their milk cow, a turkey, and a passel of little Friesens. They stood still, as if they were posing for the traveling photographer.

“Fine day!” Mr. Friesen called.

Anna waved as Top trotted past. Seems everyone is enjoying the day, she told herself. Why do I have to go to school?

She guided Top past the Friesens’ shed and down the dirt lane. It followed alongside the new barbed wire fence that enclosed the Baxters’ pastures. The schoolhouse was a mile in the distance.

Ding, ding, ding. The morning bell rang across the prairie.

Anna nudged Top into a gallop. During the last snow, Papa had read aloud from Wild Bill’s Last Trail. Mama had clucked her disapproval at the dime novel. But Anna and Little Seth, sprawled on the rag rug at Papa’s feet, had listened wide-eyed. Now Anna pictured herself chasing after outlaws, just like Buffalo Bill.

The sun was a yellow polka dot when Top Hat cantered into the schoolyard. Several girls jumped rope. A circle of children was playing Poison Snake. John Jacob was tugging Eloise Baxter’s hand, trying to pull her into the circle. If Eloise stepped on the “snake,” a rag in the middle, she’d “die” of poison.

Anna halted Top in front of the school. She could tell from John Jacob’s soot-covered face that he’d arrived early to fire up the stove. Now he was laughing and his cheeks were red beneath the black smudges. Anna waved but John Jacob was too busy pulling on Eloise, who was squealing like a caught pig.

Eloise was Anna’s age, and too stuck-up to wave. She was dressed in a green velvet cloak and matching hat. Since the Baxters had a maid, Eloise had no chores, and she was always at school early enough to play.

“Mornin’,” Anna called as she steered Top around the circle. No one paid her any mind. She blew out a frosty breath, telling herself she didn’t care.

The second bell rang. Anna trotted Top behind the school and past the lean-to used for storing wood and cow chips. “Whoa now, pony.” Sliding off his back, she tugged the headstall over his ears. The bit fell from his mouth. She looped a soft rope around his neck and tethered him to a stake near Champ, Eloise Baxter’s fancy saddle horse.

Champ nickered, glad for company. In reply, Top pinned his ears, swung his hind end around, and switched his tail menacingly.

Anna snorted. “Would you quit trying to show Champ who’s boss?” she scolded, sounding like Mama. She went over and patted Champ’s silky neck. Eloise had left her beautiful horse bridled and saddled, his reins tied to a lone cottonwood tree.

Anna frowned at the other girl’s thoughtlessness. “Least I can do is loosen your girth,” she told Champ as she let it down two notches.

Then she gave Top’s muzzle a quick kiss goodbye. “See you at recess.”

With bridle and lunch pail in hand, Anna ran around the side of the sod building. The schoolyard was empty.

She halted on the stoop in front of the closed wooden door. Late again. Miss Simmons would surely be angry.

A chill wind ruffled the hairs poking from Anna’s braid. Looking north, she noticed dark clouds gathering on the horizon. The weather was already changing.

Anna shivered. She hoped for snow, but only after Papa got home from his journey into town, Mama and Little Seth had finished their chores, and the sheep were safe in their pen.

With one last, longing glance across the prairie, Anna opened the schoolhouse door and stepped inside.

CHAPTER TWO

You’re late again, Anna,” Ida Friesen whispered. The older girl stood by the door, an open book in her hands. Ida was fourteen, and already looked a woman. The hem of her woolen dress brushed the dirt floor. Her brown hair was pulled into a bun.

“One day soon you will be a lady,” Mama often warned Anna. If being a lady meant cumbersome skirts and prickly hairpins, Anna wanted no part of it.

Ida shut the door behind Anna. Without looking up from her book she added, “Miss Simmons won’t be pleased.”

Anna ducked her head. Hurrying to a dark corner, she hung the bridle on a peg and set her lunch pail underneath. Then she pulled off her gloves and wristlets and tucked them in her pockets. When she unbuttoned her jacket, her tablet and slate clattered to the wood floor.

Anna stiffened. She peeked over her shoulder. Two rows of wooden benches stretched on either side of a cast-iron stove. Boys sat on the left side, girls on the right. The school’s one window and a kerosene lamp cast the only light. Still, Anna could see that all heads were turned. All eyes were on her.

Beyond the turned heads Anna could see the new blackboard, purchased with funds raised by the townsfolk. And in front of the blackboard stood Miss Simmons.

“Thank you for gracing us with your presence, Miss Vail,” Miss Simmons said with tart politeness. Several of the girls tittered. A few boys guffawed.

Anna didn’t bother making up a yarn. She’d already tried tales of thrown horseshoes and busted reins. Miss Simmons was from back East and had never ridden a horse, but she always managed to see through Anna’s fibs.

Anna picked up her tablet and slate and hung her jacket alongside the others. Chin tucked, she scurried to the right front bench. Miss Simmons had placed Anna between Carolina and Sally Lil. Both were eight years old. Both could read, write, and cipher better than Anna.

“Scholars, please stand for the opening song,” Miss Simmons said. “We will now sing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’.”

The students rose. Anna slid her slate and tablet beneath the bench and stood up. Hands clasped in front of her, she sang out, “O say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light, when so loudly it hail’d at the twilight’s last glea-ming?”

Carolina nudged her hard in the ribs. “Those aren’t the words,” she hissed.

“Who says?” Anna hissed back. “Didn’t it hail just three days ago?”

When the song was finished, Anna held on extra long to the last note. Miss Simmons gave her an impatient look before addressing the class. “Thank you, scholars. Miss Friesen will read from the Scriptures.”

Ida Friesen and Eloise Baxter sat on the bench behind Anna. Eloise’s father, Mr. Archibald Baxter, was the school director for the district. Miss Simmons boarded at the Baxters’ house, which was two stories and built from wood. And if that wasn’t enough to make her too big for her britches, Eloise always wore stylish dresses made by her mother’s seamstress, who lived in the big town of Omaha.

Ida made her way up the aisle and stood beside the teacher. In a clear voice, she read, “Job 28:12. And where is the place of understanding? Man knoweth not …”

Ida’s as tall as Miss Simmons, Anna thought. Last October, she’d overheard Papa and Mama talking about “the new school ma’am from the East.” Mama said she was just a child. Papa said she wouldn’t last a Neb

raska winter. So far the teacher had made it through three months and two snows. But this morning she looked a bit peaked.

Could be her corset, Anna decided, noting Miss Simmons’s tiny waist and billowy skirts. Even Mama had discarded her petticoats and corset stays.

“Thank you, Miss Friesen. That was beautiful reading.” Miss Simmons smiled as Ida walked back to the bench.

Anna cast a look at John Jacob, who sat on the boys’ side in the back row. Yesterday at recess John Jacob and Karl had talked at length about Miss Simmons’s pert figure and rosebud mouth. Now her best friend was staring dreamily at the teacher.

Anna rolled her eyes.

“Miss Vail?”

She swung around.

“Would you please come up to the front and lead the calisthenics?”

Anna flushed. Standing in front of the class was worse than having bedbugs in her underdrawers.

“Oh, ma’am, Top throwed me hard this morning so I doubt I can touch a toe.”

Miss Simmons arched one delicate brow. “Top threw you this morning.”

“That’s right.” Anna was amazed. “How’d you know?”

Giggles broke out behind her. Whirling back, Anna glared first at Eloise, then at Hattie and Ruth, sisters who also sat on the second bench and copied Eloise’s every gesture.

Across the room, John Jacob raised his hand. He stood with the older boys, Karl on one side, Eugene on the other. Eugene was sixteen and had whiskers. His pa made him work sunup to sundown, so he seldom came to school.

“I’ll lead the calisthenics, Miss Simmons,” John Jacob offered.

“Thank you, John Jacob.”

When John Jacob came up the aisle, Anna tried to catch his eye. Hadn’t they spent last Saturday together hunting prairie chickens? But he kept his gaze on the teacher. He’s smitten for sure, Anna thought crossly.

“Ready, set, and let’s begin. One … two …” John Jacob recited as he bent low. On the count of three and four he stretched high.

“One, two, lamb, ewe,” Anna murmured as she followed him. “Three, four, saddle sore.” When she raised her arms toward the ceiling, a movement by the stovepipe caught her eye.

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

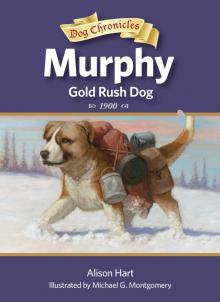

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog