- Home

- Alison Hart

Anna's Blizzard Page 2

Anna's Blizzard Read online

Page 2

The schoolhouse roof was made of sod layered on top of cottonwood poles. On warm days, the melting snow dripped through the cracks between the sod slabs. Gunnysacks hung beneath the ceiling to catch any mud raining from above, but there were no sacks near the stovepipe. Dirt sprinkled down on the kettle that steamed on top of the stove.

Anna lowered her arms again and touched the tops of her laced boots. When she rose up, she spotted a furry nose poking from a hole where the stovepipe went through the roof. Before she could get a good look, the nose popped out of sight.

A mouse trying to keep warm, Anna thought. As she bent over again, she glanced past Sally Lil. The light coming through the window was as thick and gray as dirty sheep wool.

The clouds from the north must have arrived, covering the sun. Mama called them “uninvited guests.” Papa called them cuss words. Anna hoped Top Hat was finding some dry grass to nibble. He’d need fodder to keep warm if the wind and the clouds brought snow.

“Thank you, John Jacob,” Miss Simmons said.

John Jacob made his way back to his seat. Karl was crouched in front of the stove, stoking the fire. Each week a different family provided fuel. Anna could tell by the sound of crackling corn stalks and the smell of burning cow chips that this was the Friesens’ week. With eight mouths to feed, the Friesens had no wood to spare.

“We will begin lessons now.” Miss Simmons tapped on the blackboard with her pointer. “Scholars working in McGuffey’s Sixth, please correct these ten sentences.”

Anna straightened her spine as the other children her age pulled their tablets from under the benches. “I can read as well as they can,” she muttered. She glanced at the side wall. It was covered with old sheets of the Nebraska Farmer newspaper to help keep out the damp.

Squinting, she read the bold letters at the top of one sheet: “Judge J. R. Giles Running for Mayor.” She frowned, wondering how far the man had to run to reach Mayor, a town she’d surely never heard of.

“William and George,” said Miss Simmons, directing her attention to the two smallest boys. “Miss Friesen will set your copy.”

Ida often helped the teacher with the youngest boys. She’d write several letters on their slates, and the boys would use corn kernels to outline them. “Such easy work,” Anna had scoffed to Little Seth when he’d tried the same task at the kitchen table at home. “Why, I mastered my letters last school year!”

“Third Readers please join me at the recitation table,” said the teacher.

Sally Lil and Carolina bounced from the bench. Skipping to the table, they sat on the two stools closest to the teacher. Anna dragged her feet and slid slowly onto the stool nearest the wall.

Miss Simmons held out a book with a fancy cover. Books were scarce on the prairie, and this gold-bound one looked especially precious.

“This is Poetry for Children,” Miss Simmons told them. “You will each choose a poem to memorize. Tomorrow you will recite your piece for the class.”

Sallie Lil clapped her hands. Carolina beamed.

Anna wrinkled her forehead. “Ma’am. May I recite a piece from Wild Bill’s Last Trail instead?”

“Dime novels are not literature, Miss Vail.” The teacher set the book on the table. “Now, gently turn the pages and graciously share the poems while I look over the others’ grammar lessons.”

As soon as Miss Simmons walked away, Carolina snatched up the book. “Oh, these are such wondrous poems!” she exclaimed as she flipped through.

“Let me see.” Sallie Lil crowded closer. The little girl’s hair had been hacked off and it stuck up in tufts. That meant only one thing: lice.

Anna scooted her stool a little farther away.

“Listen, Anna, here’s a poem just for you.” Clearing her throat, Carolina read aloud: “Little Anna, of all my friends I like her best, not because she is pretty or handsomely dressed; Nor is she as smart as the others I know—”

“Stop your meanness!” Anna grabbed the book.

Carolina held tightly. “I’m not through.” They tugged, ripping a page.

Sallie Lil gasped. Carolina dropped the book on the table. Her mouth formed a perfect O. An O for ornery, Anna thought, knowing that she, not Carolina, would get in trouble.

“Miss Simmons!” Carolina whined. “Anna tore a page in your new book!”

The teacher hurried over. “Oh, Anna!” she exclaimed when she saw the ragged piece sticking from the closed cover.

Anna jumped off the stool. Miss Simmons had tears in her eyes. Because of a book!

“I’m s-s-sorry,” Anna stammered. “I didn’t rip it on purpose.”

“I would hope not.” Miss Simmons picked it up and stroked the cover. “The book was a present.”

“From a gentleman?” Sallie Lil asked wistfully.

“No, Sallie Lil. It was a going-away present. From one of my teachers in Boston. She gave it to me when she heard I was hired to teach …” There was a catch in her voice, and her face grew sorrowful. “… when I was hired to teach here.”

Anna thought of Mama. Did Miss Simmons pine for Boston like Mama pined for Virginia?

Just then a gust of wind rattled the windowpanes. The sheets of newspaper rippled. The flame in the kerosene lamp flickered.

Miss Simmons paled.

Anna hurried over to the window. The glass was slick with ice. She rubbed a hole in the frost and peered outside. In the sky, dark clouds churned like waves on a stormy river. On the plain, the bristly grass bowed like churchgoers on Sunday.

Miss Simmons came up beside her. “My, how the wind is blowing,” she whispered.

“It’s blowing something fierce,” Anna replied. Then she lowered her voice, too, so the little girls wouldn’t hear. “Miss Simmons, I don’t want to worry you none, but I believe we’re in for a snowstorm!”

CHAPTER THREE

Miss Simmons nodded. One hand went to her high-necked collar. The other clutched the book to her blouse buttons. Finally she said, “I’ve survived two Nebraska snows, Anna. And we do have plenty of snow in Boston. So I guess one more storm won’t ruin me.”

“Yes ma’am.” Anna craned her neck, trying to see Top. But he was tethered out of sight behind the school.

“Now it’s time to get back to learning,” Miss Simmons reminded her. “I expect you to choose a suitable poem, Anna. Perhaps one about snow. And no more ripped pages, please.”

“Oh, no ma’am. Never again.”

“Scholars!” Miss Simmons turned, her skirts rustling like sheep in the straw. “Keep working on your language lessons. It will soon be time for penmanship.”

Ugh, Anna thought. I’d rather clean out a hog shed than work on penmanship. Anna sat back on the stool. Patiently, she waited for Sally Lil and Carolina to quit arguing over poems. The air in the small room was heavy with the smell of wet wool, musty earth, dirty necks, and smoldering cow chips.

Anna yawned. She’d been up since five o’clock. She’d had to feed the chickens and collect eggs before driving the sheep to the pasture. She rested her head on her hand. Her eyes drifted shut.

In an instant she and Top Hat were racing across the prairie. Beside her Eloise and Champ tried to keep up. Long-legged Champ was no match for the plucky Top. And when Champ tripped over a grassy hummock and Eloise tumbled off, why Anna just had to …

“Anna?” Someone tapped her shoulder, and she snapped upright. Was it time to feed the chickens already?

“I believe I found you the perfect poem,” Miss Simmons said, handing Anna a sheet of paper.

Blinking sleepily, Anna stared at it.

“It’s by Ralph Waldo Emerson. There are some difficult words, but give it a try.”

“Why, thank you, Miss Simm-m-mp—” Anna clapped her hand to her mouth, stifling another yawn. She wanted to appear pleased, not weary. She looked down at the poem, written in the teacher’s trim script.

Lips moving, Anna began to read, stumbling over the hard words as the wind shook the panes behind her:

Announced by all the trumpets of the sky

Arrives the snow, and, driving o’er the fields,

Seems nowhere to alight: the whited air

Hides hills and woods, the river and the heaven,

And veils the farm-house at the garden’s end.

The poem seemed to go on forever. Finally, Anna pronounced the last painful word. Her head ached from all the reading. Her eyes blurred. She rubbed her throbbing temples. She wished she were home, so Mama would prescribe a spoonful of Dr. Benjamin’s: a tonic for all ailments.

Miss Simmons came over to the table. Carolina and Sally Lil were still paging through the book of poems.

“What do you think?” the teacher asked Anna. “It’s titled ‘The Snow Storm’.”

“It’s a fine poem, ma’am, but I doubt I pronounced all the words correctly,” Anna said politely. “It’s a mite longwinded, too.” She glanced up at her teacher. “And I don’t believe Mister Waldo Emerson was writing about a Nebraska snowstorm. There ain’t any cuss words.”

“There aren’t any cuss words,” Miss Simmons corrected. But then she smiled at Anna, and for a moment, poor grammar and big words seemed less threatening. “Just memorize the first verse for tomorrow. You can work on the rest of it next week.”

Anna repeated the first two lines of the poem to herself over and over. She just about had them by heart when Miss Simmons announced that it was time for penmanship. Anna clutched her stomach, wishing again for a large dose of Dr. Benjamin’s.

Miss Simmons passed out the pens and ink. Anna retrieved her tablet from under the bench. Ida, Eloise, Hattie, and Ruth flounced up to the recitation table. “We can sit here because we are almost ladies,” Eloise explained to everyone.

Almost being a lady is a far cry from being one, Anna thought sourly.

John Jacob and Karl stretched out on the plank floor. Eugene stayed on the bench and balanced his tablet on his knees. Anna and the others sat Indian style on the floor and used the benches as desks. Anna shared the inkwell with Sally Lil. Carolina got her own to use.

Anna opened her tablet to a clean page. She dipped her pen in the well.

“Hold the stylus lightly, scholars,” Miss Simmons instructed as she walked around the room. “Sweep your arm gracefully.”

Anna swept her arm. Her dress sleeve wiped across her letters, smudging the ink.

“Anna, how many times must I tell you to hold the pen in the right hand,” Miss Simmons said. “That is your writing hand. Then the ink won’t smudge.”

Anna switched hands. The pen felt awkward, like she was holding it between her toes. She gritted her teeth. Carefully, she wrote a big A and a small a, then a big B and a small b. As she began the C, the pen nib stuck in a rough spot in the paper.

Frustrated, Anna pushed on the jammed point. The nib slipped and shot ink into the air, splattering the front of Carolina’s pinafore.

“Miss Simmons!” she wailed. “Anna threw ink on me!”

“I did not!” Anna jumped to her feet. Her knee hit the bench and it tipped over. Tablets and inkwells crashed to the plank floor. Anna dove over the bench and caught up one inkwell before it spilled. The second one landed on top of Sally Lil’s open tablet. A black stain spread across the white pages.

Sally Lil began to cry. “Papa said he can’t afford another!”

Anna touched the girl’s skinny shoulder. “Oh, Sally Lil, you can use mine.”

“What in heaven’s name is going on?” Miss Simmons bustled over. Anna didn’t raise her eyes. She gulped, expecting harsh words.

“Look at my pinny!” Carolina continued to wail. “It’s all Anna’s fault!”

“It was Anna’s fault, Miss Simmons,” Eloise Baxter said from the recitation table. “I saw the whole thing.”

“We did, too,” Hattie and Ruth chimed from the stools beside her.

Tears sprang into Anna’s eyes. The girls were right. It was her fault. Her fingers could pluck an egg from under a chicken without ruffling a feather, but she couldn’t get them to manage a pen.

“I’ll just leave then,” Anna declared, angry at herself and the girls accusing her. “I hate all this learning anyways!” She stomped down the aisle, jerked open the door, and ran out of the school.

She raced to the rear of the building. The cold wind whipped her braid and her skirts, but she didn’t care. Top was nibbling a clump of dry grass. He lifted his head and greeted her with a whinny.

“Oh, Top.” Anna hugged him. “I just ain’t cut out for lessons. Reading, arithmetic, penmanship. It’s all too hard. Too odious.”

She heard Miss Simmons call her name.

Anna buried her face in Top’s mane.

Footsteps crunched closer. “There you are,” the teacher said. “Come back inside before you freeze.”

Anna shook her head. “No ma’am. I’m going home and herd sheep. That’s a sight easier than penmanship.”

“My dear Anna.” Miss Simmons gently touched her arm. “I know that lessons often seem hard to you. But you’ve come such a long way this school year.”

“But I haven’t.” Anna faced the teacher. Miss Simmons had thrown a woolen cloak over her shoulders. “I still can’t write my ABCs. It’s the same way with cross-stitch. My fingers are just too stubborn.” Holding up her hands, she wiggled her fingers. “They’re like a ten-mule hitch bucking at their traces.”

Miss Simmons laughed. “That’s a creative analogy.”

“A what?”

“Anna, your mind is as sharp as this wind,” Miss Simmons said, hugging her cloak tighter. “Learning just takes time. And you shouldn’t listen to what the other girls say when they’re being hurtful. They’re just jealous because they don’t have a pony as fine as yours.”

“Eloise has Champ,” Anna murmured as she twirled a hank of Top’s mane.

“True, but I’ve never heard Eloise boast about Champ herding sheep,” Miss Simmons pointed out.

Anna shrugged.

“Will you please come back inside now?” Miss Simmons asked.

“We-e-l-l-l …” Anna drew out her answer. She considered going home. But if she did, Mama would probably send her right back. “If I stay, do I have to write anymore?”

Miss Simmons shook her head. “No. However, Anna, no matter what you decide, you do understand I’ll have to write a note to your father and mother. You will have to buy Sally Lil a new tablet. And you may have to replace Carolina’s pinafore.”

Anna winced. Mama would not be pleased. Anna’s family wasn’t as poor as Sally Lil’s. And Papa didn’t have as many mouths to feed as the Freisens. But like all other homesteaders, the Vails had to be very frugal. On the prairie, money was as scarce as trees.

“I understand, ma’am,” Anna said. When Mama found out about the spilled ink, she’d be mad enough to cut a switch. Anna decided she’d take her chances with Papa, who should be home about the same time school let out. “And I think I’ll come back to school now.”

Miss Simmons smiled. “Good. Why don’t you clean up the spilled ink while the others finish their letters? Use the old newspapers Missus Baxter gave us to use.”

“Yes ma’am.”

“Now let’s go back inside. This wind is numbing my fingers.”

Anna said goodbye to Top and Champ and hurried after the teacher.

Everyone was pretending to work when the two came into the school. But Anna could tell by their sideways glances that they’d been watching the door like hawks.

Sally Lil was seated on the bench, staring sadly at her ruined tablet. Anna gave the little girl her own to use. Then she went over to stack of newspapers piled high in the coat corner. She wadded up several sheets. While the others finished their ABCs, she wiped up the ink. This task she could well do.

“Look, Miss Simmons.” Eloise held up her tablet. She’d written How lovely is our teacher? in perfect script.

“Very nice, Eloise,” Miss Simmons said.

Anna rolled her eyes. “Tea

cher’s pet,” she muttered as she tossed the soiled newspapers into the stove.

“Everyone’s work looks praiseworthy,” Miss Simmons told the class. “When your ink has dried, please put your tablets away and get out your slates for arithmetic.”

Anna wiped her black-stained fingers with another newspaper and then went back to her place on the bench. She sat next to Sally Lil, her slate on her knees. Miss Simmons passed out the stubby pieces of chalk. “We’re running low, scholars, so bear down gently. And no chewing on the ends.” She looked pointedly at William and George.

“We will be working on subtraction this day.” She tapped on the blackboard with the pointer. Anna groaned. Problems covered every speck of the painted board.

“Who can tell us how we use subtraction in our lives?”

Eloise’s arm shot up.

“Miss Baxter?” the teacher said. “Would you give an example, please?”

Eloise hopped to her feet. “If I have ten party dresses but two need mending, how many of my party dresses would not need mending?”

Anna snorted.

“Miss Vail? Does that ladylike noise mean you would like to answer the problem?”

Anna stood. “Yes ma’am. The answer would be zero party dresses since in all my life I ain’t never had one.”

Beside her, Sally Lil nodded in agreement.

“And I have no earthly idea why Eloise would need ten of them,” Anna added for good measure. “There ain’t that many parties for her to go to. Ten sheep would be more practical.”

“It’s just an example,” Eloise retorted.

“Miss Simmons, I have an example,” Karl called.

The teacher sighed. “Yes, Karl. Please share your example.”

“A homesteader has thirteen chickens in the coop. A coyote breaks in and kills—”

“Thank you, Karl,” Miss Simmons quickly interrupted. “I think those are enough examples. William and George, please bring your slates to the recitation table. Scholars, please copy the problems on the blackboard. First Level do numbers one through five. Second Level …”

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

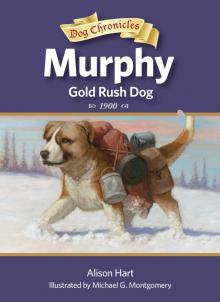

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog