- Home

- Alison Hart

Gabriel's Journey Page 5

Gabriel's Journey Read online

Page 5

Still, I’d hoped Union soldiers would be different. Ain’t they fighting to free the slaves? Why then are so many of them dead set against having coloreds in camp? Then I remind myself that Captain Waite has been mighty helpful to me and my pa, and Colonel Brisbin is an abolitionist, which I gather means he cottons to black folks. At least there’s a few Yankees who ain’t like the lieutenant.

That thought cheers me as I follow Captain Waite. I’m in sore need of some cheering up after my less-than-cordial reunion with Pa. He’ll come around, I know. I just have to convince him that I belong here with Company B.

* * *

The next morning finds me nestled in a bed of sweet-smelling straw in an empty horse stall. I’m half-asleep, my blanket over my head, when something pokes me in the side. Flinging off the blanket, I leap to my feet, fists clenched, ready to smite skeletons and corpses. Only it’s just Pa, leaning on a pitchfork.

“Think you’re still in Saratoga fighting those bullies?” he asks.

I shake my head sheepishly. “No sir.”

“You slept through reveille and the call to breakfast.” He tosses the pitchfork and I catch it by the handle. “You’ll have to clean stalls on an empty stomach.”

“But Pa—”

“I ain’t Pa no more.” He gives me a stern look. “I’m Sergeant Alexander, your superior, and you will obey orders without question. Do you understand?”

I nod.

“Company B has about sixty men, divided into squads. I’m sergeant of the 1st Squad. We’ve sixteen men. That’s sixteen horses and sixteen stalls. You’ll muck, lime, and bed them all by tonight.”

“By tonight?”

“Without question!” he barks.

I startle. At Woodville Farm, Pa and me worked side by side every day. Never once did I hear him yell.

“Stalls will be empty this morning because we’re having mounted drill. Do the mucking then. Wheelbarrow’s at the end of the stable by the manure wagon. Tonight, you’ll help Private Black feed the horses. He’ll show you the rations. Tomorrow you’ll help Private Crutcher. Make sure you rise before the sun. Any questions?”

I throw back my shoulders. “No sir!”

He leaves without another word.

As soon as the stall door shuts behind him, my shoulders droop. I kick my blanket into the corner. I know why Pa’s acting like a drill sergeant. He’s hoping I’ll scurry back to Woodville Farm like a whipped dog.

Only that ain’t going to work. My pass from Colonel Brisbin is in my pocket and I’m determined to be a soldier.

Thrusting the pitchfork like a sword, I attack the wall. “Take that, you Rebel vermin!”

“Whoa, boy.” Private Black rests his arms on the top of the stall door. “Save that for the real graycoats.”

I perk up. “We fightin’ them soon?”

He laughs heartily. “Yes sir. Right after we sweep the aisles, dig the wells, and clean the privies. Oh, and learn us how to fire rifles.”

“You ain’t fired a rifle yet?”

“You see any rifles when we were drilling yesterday?”

I shake my head.

“Captain Waite promises us broomsticks for tomorrow’s practice.” Again, the private breaks into laughter, and I can’t help but join him. “I’ve got a present for you.” His eyes twinkle as he pulls something from his back pocket. It’s a Yankee kepi. He tosses it on my head. “Belonged to the drummer boy.”

“Thank you!” I settle the cap on my head, avoiding the question of what happened to the drummer boy.

“Now you look a real soldier.”

I hear the notes of a bugle.

“That means ‘to horse’,” Private Black explains. “A good cavalryman has to learn the commands signaled by the trumpeter. Come on.” He gestures for me to follow. “I’ll show you ’round.”

Unlatching the stall door, I jog after him. The last two soldiers are leading their mounts from the stable.

“Don’t worry ’bout your pa,” Private Black says as we walk down the aisle. “He’s a good sergeant. The men in our squad respect him. He should be captain of Company B, but ain’t no colored officers allowed. Cap’n Waite means well, but I believe that boy’s just left his mama. Luckily your pa and Reverend Fee keep up our spirits. The reverend not only preaches, he works hard to get the colored soldiers supplies and respect.”

I nod. “I’ve heard of the reverend.”

“Your pa’s good with the men and the horses,” Private Black goes on. “And we do need someone who knows horses. Most of these men who used to be slaves ain’t even been on a mule before.”

I slip in a brag. “Pa trained racehorses.”

Private Black chuckles. “No breds for the colored soldiers. Me, I’ve been assigned a slab-headed roan I named Hambone ’cause he’s so pigheaded.” He stops in front of the last stall. It has a barred top door, like a jail cell. “This here’s Champion, Cap’n Waite’s mount. I call him Devil.”

I peer through the bars. Champion is a sixteen-hand stallion, as glossy and black as a crow except for a brilliant white star. He’s a Thoroughbred, no doubt confiscated from a Rebel owner’s stable. When he sees me watching him, he pins his ears and lunges, raking his teeth against the iron bars.

“That horse is rank. Cap’n Waite don’t ride him enough.” Private Black lowers his voice. “I believe the captain’s a mite scared of him. Not that I blame him. Your pa appointed me the horse’s groom ’cause of my experience. Devil here and me get along fine as long as I carry an ax handle and don’t turn my back on him.”

“You worked with horses before?”

“Yep. I’m a teamster. The Yankees impressed me into labor when Camp Nelson was first built, and I drove many a wagon to Tennessee. I got tired of looking at the backside of a horse, so I enlisted as soon as President Lincoln made it law.”

Hooking my fingers through the bars, I study Champion. I can read a horse like Annabelle reads a book. There’s a glint of fear in Champion’s eyes that tells me his story: he’s been whipped too many times. Now his gnashing teeth and flat ears say, “Stay away. I don’t want to be hurt no more.”

The horse don’t need an ax handle. What he needs is a soft touch.

“I’d like to be Champion’s groom,” I say.

Private Black shrugs. “Far as I’m concerned, he’s all yours. I’d rather be on the field drilling with my squad than tussling with that crazy animal. Only it ain’t up to me.”

We walk outside, where he shows me the wheelbarrow and manure wagon. A wooden ramp slants from the ground to the wagon’s end gate. “Don’t fill your barrow too full or you won’t get it up that ramp. Now, I got one more order.” He stoops to whisper in my ear. “There’s a plate of syrup-soaked cornbread hidden on top of a trunk in the saddle room, so eat up. Soldier works harder on a full belly.” He winks. “Just don’t tell your pa.”

Private Black will be a good friend, I think when he leaves. As I pick up those wheelbarrow handles, I hear shouting on the other side of the barn. A number of saddled horses are walking two by two in the fenced area in the center of the four stables. A soldier holds the reins of each horse. I see Corporal Vaughn standing slightly apart. Pa’s in the front of the arena, mounted on a handsome chestnut. I immediately recognize Hero, Mister Giles’s Kentucky Saddler that he gave to Pa in thanks for saving his Thoroughbreds.

“Attention!” Pa shouts. “Stand to horse!”

Instantly, the soldiers line those horses into rows. They stand smart on the left side, right hands holding both reins below the horses’ muzzles, and stare straight ahead.

All because of a command from my pa.

Pride fills my heart. I lower the wheelbarrow. Raising one stiff hand to my forehead, I salute him.

Chapter Six

Five days later finds me still mucking stalls. It’s evening, and the horses are in the lots. The stable’s quiet as I run the last wheelbarrow full of manure up the ramp as fast as I can. It wobbles unsteadily, tips, and d

espite my straining, the wheelbarrow pitches into the wagon bed, along with the manure.

I curse the wheelbarrow, curse the army, curse the maggoty bread and rotten salt pork they give us to eat, and most of all, I curse the dirty stalls.

Worn out, I slump on the top of the ramp and bury my head in my arms. Pa ain’t let up. Sixteen stalls a day for five days adds up to . . . ? I search my mind, but can’t find the sum. To think, it wasn’t so long ago that Annabelle and me were counting up my purse winnings—over two hundred dollars, which Mister Giles put in a bank for me.

Thoughts of Annabelle make me wonder what she’s doing. I ain’t seen her or Ma since I left them that first day. Every night I’m so weary I drop like a feed sack into my straw bed. Perhaps a few days of washing dirty linens sent her scurrying back to Woodville Farm without a goodbye, and I won’t ever see her again.

Sorry burns my eyes. The only high point these past days has been grooming Champion. The stallion should be winning races, not locked in a stall day and night. I don’t officially have permission, but when I’m alone in the barn late, I slip into his stall. Humming, I brush that horse until his coat shines. I’m sorely tempted to leap on him one night and gallop him in the moonlight. But I reckon that would get me kicked out of Camp Nelson for sure.

“Gabriel? Is that you?” a voice calls from the bottom of the ramp.

I jerk my head from my arms. Annabelle’s staring up at me, her lips parted in astonishment. I scramble to my feet, slip on the manure-slick wood, and topple head over heels to the bottom of the ramp.

“Oh! Are you all right?” Annabelle’s all sympathy as she helps me to my feet. But then she wrinkles her nose and fans her face with her gloved hand. “Have you been bathing in horse droppings?”

“Ain’t been bathing at all,” I reply crossly, mortified that Annabelle found me a filthy stable boy instead of a proud soldier. Frowning, I pick up my kepi and whap it against my leg to shake off the dirt. “I thought you’d be long gone from here.”

“Why, no!” Annabelle exclaims. “Why would you think that?”

I shrug, noticing that instead of being beaten down by scrubbing, she’s bright-eyed and sweet smelling. Her hair’s fashionably rolled in a bun and covered with netting; her faded calico’s draped with a comely shawl. Only her dingy gloves suggest she’s been working.

“Indeed, I’m having the most exhilarating time!” she declares. Waltzing back and forth beside the wagon, she gushes on and on about the camp “being splendid,” as if we’re conversing in a parlor instead of a stable yard.

“Annabelle,” I interrupt, my voice low, “it ain’t proper for a lady to be sashaying around the stables unescorted.”

“For your information, I have two chaperones,” she huffs, pointing a gloved finger over my shoulder.

I turn around. Pa and Ma are strolling beside the fence enclosing the horse paddocks, their arms linked as if they’re courting.

“And your pa’s your superior, so you better mind your manners,” she teases, before switching the subject. “Have you met Reverend Fee? He’s been running Camp Nelson School for Colored Soldiers. He’s helping me establish a school in the tent city where your ma and I live.” Annabelle swings to face me, her eyes glowing. “Gabriel, every day I get to teach! Not in a real schoolhouse, mind you, but in a tent just for learning. Reverend Fee has provided benches, and he’s procuring books and tablets. Oh, he’s a man of unlimited ambition! He’s talking about building a government camp for the soldiers’ families, too. Reverend Fee has such heavenly ideas that I believe he may be a saint!”

I fold my arms against my chest, listening with a doubtful and jealous heart.

Annabelle keeps bragging on and on about Reverend Fee. Finally she stops pacing. She turns to me coquettishly. “And how have you fared the past five days? Your ma and I hoped you would visit us.”

My tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth. I’d love to lie and tell Annabelle I’m too busy fighting Rebels to have tea in her tent. But I’ve never been a liar, and I ain’t going to start now. ’Sides, Annabelle can clearly tell by my shabby britches—the same ones I was wearing when we arrived—that I ain’t no soldier.

Still, I don’t have to let on that I’m nothing but a muckworm. Setting the kepi on my head, I adjust it at a rakish angle. “I’m the stable hand for Pa’s squad,” I tell her. “I help care for their horses, so I ain’t had time for social visits.” I want to puff myself up even more, but I’m too yellow.

“My, that sounds like a lot of responsibility.” Annabelle says, and I’m surprised there’s no mockery in her voice.

“I can show you the stable,” I venture, doubting she’ll accept. I can count on one hand the number of times Annabelle visited the barn at Woodville Farm.

She smiles. “I’d like that.”

“The horses ain’t as grand as Mister Giles’s Thoroughbreds.” As we walk down the aisle, I shy away from her, since I’m grimy from head to toe. But when we reach Champion’s stall, she moves so close that her skirts brush my toes.

“Except for Captain Waite’s mount, Champion, who appears h-highly bred,” I stutter.

She peers through the bars. “Oh, he is so handsome!”

“As handsome as your Reverend Fee?” I blurt out the words before I can stop myself.

She slants her eyes at me, a smile playing across her lips. “Why Gabriel Alexander, I do believe I note a hint of jealousy in your voice.”

My cheeks flame beneath the smudges of manure. “That’s because he’s all you’ve talked of so far!”

“Or perhaps his name was all you heard,” she murmurs. “I also spoke about teaching. Every day my thoughts get stronger on the matter,” she continues. “You soldiers may believe that fighting and killing are the way to freedom. But I believe reading and writing are more powerful. That’s why white folk don’t allow us to be taught. They’re afraid that if coloreds are educated, we’ll refuse to be kept as slaves.”

I stare at Annabelle, speechless. She has no idea of the importance of the soldiers she mocks, and yet I can’t find the words to argue. Why does she always render me mute like this?

Fortunately, Champion saves me from further humiliation by crashing against the door. Startled, Annabelle screams and stumbles backward, and for a moment I grasp her elbow to keep her from falling.

“My, he’s rather fierce,” Annabelle declares as she backs away.

“Naw, he’s a lamb,” I boast to hide my awkwardness. Mustering a dust-speck of courage, I say, “After I show you the horses, I’d like to walk you home. That way you can show me your teaching tent on the way.”

Annabelle smiles. “I’d like that, Gabriel. You know, your ma and I have missed you. I’ve missed you,” she says softly.

I stop dead in my tracks. Annabelle continues up the aisle, sashaying from one side of the aisle to the other as she peers curiously into the stalls.

I open my mouth, wanting to say that I’ve missed her, too. But all I can do is stare, spellbound by the tuck of her waist and the flare of her skirts as they sway with each delicate step.

* * *

The next evening I work like fury to finish those stalls. Tonight, I’m determined to see Annabelle again and get a glimpse of that know-it-all do-gooder Reverend Fee. Annabelle’s teaching a class, and I aim to be in the first row. Not to learn, mind you, but to keep an eye on the reverend.

I’ve one last stall to muck, and then I’m heading to the wash tent for a bath and change of clothes. Private Black’s promised me a chunk of soap and a tub of clean water, not scummy thirds.

I’m forking wet straw into the wheelbarrow so fast that I barely hear someone call my name.

“Gabriel, could you assist me?”

Without stopping my work, I glance up. Captain Waite is standing in the aisle. A saber in its scabbard hangs from his sword belt at his left side. On his right side, the grip of a revolver juts from a leather holster. Sharp spur rowels poke from the heels of his polished boots,

which rise to cover his knees, and a slouch hat covers his head.

Dropping the pitchfork, I snap to attention, even though I ain’t a real soldier. “Yes sir! I await your orders!”

“I need Champion tacked up, but Private Black is nowhere to be found. And I’ve heard enough stories from your pa to know you’re right handy with a horse. He even showed me a newspaper clipping about your win in Saratoga.”

I bite back a grin, pleased that he saw my name in the paper. “I’m at your service, Captain,” I say, all thoughts of Annabelle wiped from my mind. Eager to get the job done before Private Black appears, I dash to the supply room. I know exactly where to find Champion’s tack, since I oiled the Grimsley saddle this morning.

I slip the saddle from the rack and grab a clean blue blanket with a gold outline. Captain Waite has picked out a cumbersome bridle with two sets of reins and a bit with a high port and long curved shanks. I shudder at the sight of it. From all my work with Champion, I’ve learned two important things: The horse is smart and sensitive, and he reacts to pain with meanness. Sharp rowels and long shanks? No wonder he bucks.

Do I dare make a suggestion to the captain?

I think back to Pa’s words from my first visit to Camp Nelson: Most officers don’t want advice from a colored man. But then I remember something else Pa told me. You’ve got to have a man’s respect before you can teach him anything. I glance at the captain, who’s unbuckling a bridle strap. I gained Champion’s trust and respect, so now I need to take another gamble. If I can win the captain’s respect, I might not have to muck stalls forever.

I clear my throat. “Captain, sir. Permission to speak.”

“Permission granted.”

“I . . . um . . . it’s about . . . it’s just that—”

“If you have something to say, Gabriel, spit it out.”

“Yes sir. I’ve been grooming Champion every night, getting to know the horse. The others call him ‘Devil’, but I don’t agree. I might have a few ideas to help you ride—”

I cut off my words quick. Now I’ve done it. I’ve dared to suggest that an officer can’t ride his own horse. I might as well join the corpses in the dead house.

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

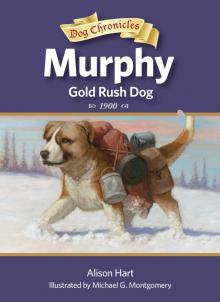

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog