- Home

- Alison Hart

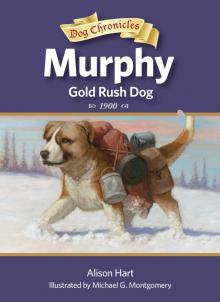

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog Page 4

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog Read online

Page 4

“What can I trade for the mukluks?” Sally mused aloud as we walked past the stores. “Our money does not mean much to the Inupiaq.”

We passed the bakery. Lifting my nose, I sniffed deeply. Sally’s eyes brightened. “Of course! See-ya-yuk and his family love freshly baked bread.”

The bell over the door rang when we went into the bakery. “Hello, Mrs. McConnell.” The tall woman behind the counter wore a white apron over her long skirts. She smelled as heavenly as Miss Althea at the saloon.

Sally purchased several loaves and tucked them in her satchel. “Mrs. McConnell, if you were mining gold on the Snake River, what would you take?”

“A bag of biscuits. They keep forever and are still delicious even if they get hard or wet. Plus your dog loves them.” Plucking a biscuit from its stack, Mrs. McConnell tossed one to me. I snatched it from the air and gulped it down in one bite.

“I will keep biscuits in mind.” We left the bakery and turned down an alley. Behind the rows of buildings on Front Street, the tundra stretched for miles like a green sea.

I led the way up the path that wound from town. The frozen earth had partially melted under the hot sun, and my paws squished into the mushy ground. Around us, the hills were colorful with wildflowers. Sally picked handfuls of phlox and wild geraniums, which grew among the tundra grass. I dug in the sweet-smelling violets, kicking dirt in the air.

“Oh look—the first blueberries of the season!” Sally said after we had walked about a mile. The squat bushes were scattered in a brushy area of willow. “We’ll pick some on the way home for dinner tonight, Murphy. Though a handful now sure would taste wonderful.”

Plopping beside Sally, I delicately plucked a clump from a twig.

She giggled as she filled her own mouth. “You are like a bear, eating whatever you can find. Which is good. When we are on the claim on the Snake River, we will be living off the land.”

See-ya-yuk’s dogs let out a terrible racket as we approached the family’s summer home, a tent made of skins. Small and wolflike, they charged toward us, hair bristling. My own hair rose, but I ducked behind Sally to get away from them.

She swatted at them with her satchel. “Go away, you foolish dogs,” she scolded. “Or you will get no bread heels.”

See-ya-yuk ran over, a grin filling his brown face. He wore mukluks, boy’s breeches, a fur vest, and a wool military cap. “Sally! Your boots are ready. They are in the ee-nih.”

Sally clapped her hands together. “Thank you! And I brought you a present too.”

See-ya-yuk raced to Sally’s side and yanked open her satchel. The natives were always curious and would even come uninvited into Sally and Mama’s tent if I did not bar the door.

“Aye-ee!” See-ya-yuk pulled out a bread loaf.

Carrying the bread, he raced to his home, shouting for his mother. The dogs chased after him, forgetting about me, and I barked at their retreating tails.

Sally laughed. “Save your false bravado for bears and wolves,” she told me.

See-ya-yuk’s little brother toddled out from the triangle doorway and over to us. I licked Wee-lil-tuk’s cheek; he always tasted like seal liver, my favorite. Squealing with laughter, he fell on his bottom.

Sally pulled off her bonnet and handed it to him. Wee-lil-tuk put it backwards on his head, which made her laugh.

See-ya-yuk popped his head around the tent flap and proudly held up the mukluks his mother had made. “For you, Sally.”

“Oh!” she gasped. “They are beautiful! Please tell Nee-ok-see-na how much I like them.”

The boots were made of walrus hide. The skin on the outside was pliable and waterproof, while the fur on the inside was soft and warm. Sally and I had watched See-ya-yuk’s mother as she worked on them, shaping the skin with her teeth. Sally had practiced too, which is how she had learned how to make the straps for my harness. My own mouth had watered as they worked, until Nee-ok-see-na had laughingly thrown me a chunk of seal meat to chew.

“I’ll never wear my stiff old boots again.” Sally sat on the ground and pulled off her gum boots.

See-ya-yuk’s eyes widened. “For me?” he asked, lifting the boot she had taken off.

“If you can fit into them.” Sally handed him the second boot.

He attempted to fit one over his foot. “Small,” he said solemnly. Whipping his knife from his belt, he split the end of the boot and shoved his foot inside. His toes wiggled. “Fits!”

See-ya-yuk put the other boot on and then rose and danced around. I woofed, the native dogs howled, and Wee-lil-tuk squealed as Sally danced in her knee-high mukluks.

Nee-ok-see-na emerged from the tent, bringing everyone—even me—bread slices slathered with fat. We ate heartily.

“Now aqalugniaqtuq—fishing,” See-ya-yuk said, licking the fat off his fingers. Sally picked up her satchel and we headed down to the river. By the time we reached a quiet spot on the Snake, the sun was high in the sky.

“I’ll surprise Mama with fish and blueberries for dinner.” Sally threaded a sliver of tomcod onto the hook. She knew well how to bait the bone hook and cast out. But often she lost her trout or grayling before bringing it to shallow water. I tried to help, catching them in my mouth when I could. But fish are slippery and wiggly, and usually I lost them too.

I waited in front of her, my paws in the cold, swirling water, my eyes searching for a flash of silver or red.

See-ya-yuk was a patient and quiet fisherman like me, but Sally was as noisy as the native dogs who crashed about on the shore yelping at hares. “See-ya-yuk!” she called. “I see gold in the water. Wouldn’t it be better to fish for gold instead of trout? Then you could buy a two-bedroom cabin for your mother. Isn’t that a nugget by that rock?”

See-ya-yuk nodded but kept his eyes on the bobbing chunk of wood tied to his line. As the sun sank lower, he pulled in fish after fish.

“This would not even feed Wee-lil-tuk.” Sally stared at the one fish that she had caught. “I must get better at fishing if we are to survive on our own.”

See-ya-yuk handed her a large trout that he had caught. “For Mrs. Dawson,” he said with a grin.

“Mama will appreciate this. Thank you.” Sally wrapped her two fish in oilcloth and tucked them in her satchel. She waved goodbye to See-ya-yuk and we headed down the trail. The dogs followed us for a while, snapping playfully at my tail. I tucked it between my legs until they grew tired of the game and left.

As we walked, Sally picked up fallen branches and tied them to both sides of my harness. Soon I was loaded down with sticks while the bucket still clanked on one side.

When we reached the patch of blueberry bushes that grew on a sunny hillside, Sally untied the bucket. She picked berries, tossing them into the bucket as she sang a song, timing the words with each plink. I ate berries straight off the bushes.

Twigs snapped, startling me, and I spun around. A moose stood over me, its head lowered. I could tell by her flat ears and the raised hair on her hump that she was angry. I knew a female moose will not usually attack—unless she is protecting a calf.

Slowly I backed up, my gaze searching for a sign of her young. Moose have big flat hooves that can strike hard, and I did not want to get pummeled. Then I saw the calf, flicking its ears at the flies. It was on the other side of Sally, who was bent over intently searching for ripe berries. We had not seen it as we picked because it was half-hidden in the brush.

My heart began to pound. Sally was directly between the moose and her baby!

CHAPTER NINE

A Sudden Change

August 5, 1900

Grabbing Sally’s long skirt in my teeth, I yanked her out of the path between the moose and her calf. The cloth tore and she fell. Her bucket tipped over and blueberries scattered everywhere.

“Murphy!” She swatted me on the nose.

Sally had never hit me before, and the pain startled me. For an instant, I remembered my days with Carlick and was filled with sadness, but then the

moose stepped closer to us.

She swung her head from side to side, glaring and my heart quickened. Just then the calf struggled to its knees, rump in the air, and rose on its gangly legs. I barked, trying to warn Sally.

Startled, she turned and saw the calf and its mother. Stifling a scream, she crawled from the bushes and up the hill as fast as she could.

I barked again. My hair bristled and I backed down the hill away from Sally in fear.

The moose leaped, her forelegs pawing the air. I darted away, the firewood banging my side, and ran past the calf. The moose galloped after me, crushing the brush in her anger.

From the corner of my eye, I saw Sally scramble to her feet. Grabbing the bucket and satchel, she ran up the hill and disappeared over the side.

I raced on, trying to get away from the mama moose, blundering through brambles and flowers. The wood on my harness caught on branches and ripped from the straps.

Finally I could no longer hear the moose. Panting and tired, I slowed. When I looked back, she stood over her calf, lovingly cleaning it with her tongue.

Relief filled me. Now I had to find Sally. I trotted up the hill, giving the moose and her baby a wide berth. Dropping my head, I caught her scent, which zigzagged through the brush.

“Murphy.” I heard a low call. She stood up from behind a hillock and waved urgently. I ran up to her and she gave me a hug. I wagged my tail and whole rump with joy. “I’m so glad you’re all right. Thank you for saving me. I didn’t see the moose or her calf until you barked.”

I licked her face, which was pale. Usually Sally was brave, so I was surprised to see her cheeks so white.

She took my head in her trembling hands. “I am so sorry I hit you. How could I have doubted you? It will never happen again. I promise. The boys in town were wrong, you aren’t a scaredy-cat.”

Only I was. I ran from the moose just as I had run from other dogs, the boys in town, and Carlick. But since it had chased me instead of Sally, she had been able to get away.

“What happened to your dress, young lady?” Mama asked when we finally returned. She stood in front of a smoky fire outside our tent, and I could smell beans and beef simmering.

“My dress?” Sally echoed. Her white pinafore was streaked with mud and her flowered skirt was ripped where I had grabbed it. Before coming home, she had again picked up more sticks and tied them to my harness. But we had lost all the blueberries.

“Where is your bonnet, what are those things on your feet, and where have you been?” Mama’s voice rose high and tight like the day she had given Sally a shake. I slunk to the other side of the fire, wanting to get away.

“I was fishing.” Sally pulled the oilcloth-wrapped fish from her satchel. “And collecting wood. The driftwood on the beach is about gone. You needn’t have worried. Murphy was with me.”

Mama didn’t even glance my way. For a long moment, she stared at Sally. When she did speak, her voice had dropped to almost a whisper. “Look at you, my lovely daughter. Your hair is tangled and your skin is as brown as a native’s. And instead of being a Gibson girl, I am a mess too. My one good dress has been ruined, and my fingers are sore from typing all day. Our house is filled with sand, and the sides flap and the roof leaks during storms. Grandmama was right. We never should have come to Nome.”

“Grandmama was not right,” Sally protested. “I love it here. Yes, it is wild and cold and we live in a tent. But the tundra is beautiful and you should have seen the blueberries. We would have brought you a bucketful, only the moose—”

Sally caught herself, but not before Mama heard her. Her face drained of color. Then slowly she turned away from her daughter, bent over the pot, and stirred. “Supper is ready,” she said tightly. “I am not hungry and have typing to do before I retire.” With sagging shoulders, she went into the tent.

Sally’s lower lip quivered as she watched her mother go. “It’s all right, Murphy.” She untied my harness straps. “It’s just that Mama works day and night. She’s more tired than angry. She’s right about the tent, though. We must find gold so we can buy a cabin. Come. Let’s fry these fish. A good meal will make her feel better.”

But a good meal didn’t tempt Mama. Rapid click-clacking came from the tent, and no amount of cajoling on Sally’s part would persuade her mother to stop typing and come eat. Much to my delight, I got to eat a whole fish, plus part of Sally’s, for now she wasn’t hungry either.

When the frying pan had cooled, I licked up the last of the lard. Then Sally washed it with water and sand. By the time we had finished, the sun was lowering for the night.

When we returned to the tent, Mama stood outside with a creased piece of paper in her hand. “I have written to your grandparents, Sally,” she said. “I have told them that we are booking passage on the Lucky Lady for home.”

For an instant Sally was too stunned to speak. “Y-y-you mean leave Nome?” she stammered. “But Mama, we can’t. I love it here.”

“Tomorrow I am buying tickets. The steamship leaves August 7; that’s in four days. We will arrive in Seattle by the end of August. We may miss your Grandfather’s arrival here in Nome, which is unfortunate, but I will leave word for him. Grandmama will be triumphant that we have given up, but I will deal with her.”

“Mama, no!” Sally cried out. “This is my home, not San Francisco.”

I whined anxiously, hearing the emotion in their voices. Things had been so right since I met Sally and Mama. Now suddenly they were so wrong. And I didn’t know how to help.

“It’s done, and I will hear no more of it,” Mama said. “Now pack a valise. We are going to the bathhouse to wash ourselves and our clothes. We may not be Gibson girls, but we needn’t smell like beggars.” She pointed the letter at me. “That goes for you too, Murphy,” she added before disappearing into the tent.

I lowered my head at Mama’s stern words. But when I glanced over at Sally, her eyes were narrowed and her lips were pressed firmly together.

As she stared after Mama, her fingers found my head. She stroked my ears just the way I liked and said in a low voice, “I believe our plans have changed, Murphy. We must stake our claim sooner than I thought. I am not leaving with Mama on the Lucky Lady. As soon as my gear is ready, we are off to the Snake River to find gold.”

I understood the word “gold,” but I did not know the rest of Sally’s words. Still I shivered, sensing that what had just happened between Mama and Sally would forever change all our lives.

CHAPTER TEN

Up the River

August 7, 1900

Sally and I were ready to set out at midday, laden with supplies. My harness was heavy, packed with two rolled up oilcloths, netting, a rope, a scoop, a mining pan, a frying pan, and a lantern. Sally carried food, fishing gear, utensils, matches, candles, a wool blanket, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and clothing in a canvas pack on her back. She had mittens and jacket looped over her belt, as well as a knife in a sheath. Gone were her pinafore, bonnet, and boots. Instead she wore mukluks, leggings under her skirt, and a brimmed hat onto which she had sewn mosquito netting. Sally left a letter for Mama and we headed up the beach.

Mama had not changed her mind about leaving Nome. In the last two days Sally had packed bit by bit in secret whenever Mama was at work, and each time I tried on my harness, it grew heavier and heavier.

We both banged and clattered as we walked to the dock that jutted into the Snake River where it met the Bering Sea. There we climbed into a boat pulled by a team of four dogs. The dogs clambered along the riverbank, occasionally splashing in the water while a boatman stood in the bow, using a long pole to keep the hull in deeper water and away from the shore. There were many barrels and crates on the boat, but no other passengers.

“Where are you and your dog headed, miss?” the boatman asked after introducing himself as Mr. Lindblom. “You appear to be packed for a long trip.”

“As far as we can go upriver,” Sally said. “Where is your last stop?”

&n

bsp; “Usually two miles inland,” he told her. “That’s where I drop the last supplies.”

“I would like to pay you to go beyond that spot—as far as you can.” She held several coins out to him.

Staring at the coins, Mr. Lindblom raised one brow. “Does your papa know you are out and about on your own?”

“Thank you for your concern.” Sally sounded as grown-up as Mama. “I am heading upriver to my father’s mining camp now. And I am not alone.” She draped her arm over my neck. “I have Murphy.”

“Your papa’s beyond Point Crossing?” he asked.

Sally nodded. “Yes. It will be a hike from there, and my dog and I would be grateful for a boat ride as far as possible.”

“We-l-l-l…” He scratched under his sweaty hat as he thought. “The river is high, but as soon as the bottom of the boat scrapes, I will have to let you off on shore.”

“Thank you, sir.”

For a few minutes the boat surged up the Snake, with only the noise of the barking dogs filling the air. The shore was dotted with signs of miners—piles of rubble, rusting machines, broken pilings—but few men were working. Sally kept her arm around my neck. I leaned against her and felt her tremble. Was she as worried as I about this strange journey?

I began to pant. The day had warmed and I was hot under my harness. As if Sally understood, she loosened the straps and let the harness fall to the bottom of the boat.

“Not many miners up the Snake,” Mr. Lindblom said. “Most are on Anvil or Dexter Creeks where the richest placer claims have been found. Although McKenzie and Carlick have two large mines upriver. Your pa with them?”

“No, sir.”

“That’s good. Best to steer clear of anyone from Alaska Gold Mining Company. Heard there’s trouble coming for that lawless crew.”

Sally’s arm tightened around me. “What kind of trouble?”

“Owners of Pioneer and Wild Goose Mining have hired lawyers to stop McKenzie, Carlick, and Judge Noyes from stealing claims. The law is slow, though, so in the meantime, that crooked bunch is gutting as many mines of gold as they can.”

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog