- Home

- Alison Hart

School Rules Are Optional Page 4

School Rules Are Optional Read online

Page 4

While I wait for Peter, I start thinking about Githa. I hope she hasn’t left. I wouldn’t blame her if she had. It’d be like sharing a workspace with one of those spiders that eats whole chickens. I stand there for a bit wondering where Peter is and what he even looks like. The girl with the long hair is twirling a piece of it around her finger and chewing gum. In the office. What is she thinking? Miss Creighton is busy shouting out instructions, seemingly to herself, until a young guy comes out from the sick bay/paper-shredding area. He’s wearing a suit and tie. Only Mr Wilson wears a suit and even then, only when someone important is visiting the school – which is hardly ever. The tie has a zigzag pattern on it like one of those puzzles where if you look at it for long enough you can see a picture in 3D. Pinned to the zigzag tie is a gold staff badge with his name, ‘Roland’, and underneath that, ‘Office’. He must be doing some kind of workplace experiment. Maybe his boss set him up to work with Miss Creighton in an effort to put him off office work forever, for some reason.

Miss Creighton’s giving Roland about a month’s worth of jobs to do before recess. He already has that worried expression that everyone gets around her. I stand there for a bit not knowing what to do when Miss Creighton yells without even pausing, ‘Well? Are you two just going to hang around here all day? Go outside now or you can both visit Mrs Overbeek’s office.’

The only way you can tell she’s not still yelling at Roland is she says, ‘You two.’ There’s no break or anything. She doesn’t even look up. The girl with the long hair stands up slowly and I follow her out into the courtyard. We’re about two steps away from the office and she starts typing at an imaginary computer.

‘Well? Are you two just going to hang around here all day? Go outside now or you can both visit Mrs Overbeek’s office.’

I try not to look impressed, but her Miss Creighton impersonation is really good. And so close to the office!

I tell her, ‘I’m meant to be doing Enviro with Peter.’

She says, ‘You are. I’m Peta.’

I must be looking blank because she says, ‘Peta … P-E-T-A.’ She points at herself.

‘Ohhh.’

We get to the bike shed and realise we haven’t got the key. Peta goes back up to the office to grab it like it’s no big deal.

She must be immune to fear.

We eventually open the bike shed and pick up a rubbish claw each and two big garbage bags. I start to pick up stuff but Peta walks along scraping her claw along the concrete. It’s really annoying and it’s making me nervous. We have to produce a bag full of rubbish at recess. She better not be planning to take some of mine. When we reach the water tanks along the fence, she grabs my arm and drags me over to the two rubbish skips that we’re not allowed to go anywhere near.

She glances back towards the office. ‘Can you keep your mouth shut?’ Before I can answer, she’s climbing up onto the edge of the bin and filling her bag with rubbish.

Genius.

I climb up and start putting stuff in my bag too. The bin is pretty gross, full of old wrappers and food and it really stinks, but it’s a great idea and I wish I’d thought of it. When our bags are about half full, Peta says, ‘That’ll do. It’ll look funny if we have too much.’ She jumps down off the skip and waits for me.

The rest of the morning we muck around on the equipment. Peta is okay. She says she has five brothers. Five. They’re all older than her. Three of them don’t even live at home. I can’t believe she has five brothers … maybe I should stop complaining about the one I have.

At recess, Miss Agostino is so impressed by how much rubbish we’ve got in our bags, we get an icy pole and a lamington each. I notice Ian is working with Miss Agostino today. He’s eating a lamington too, even though I bet he didn’t pick up anything.

I tell Peta she can hang out with Alex and me until she makes some friends. I’m thinking we could really pick up some good ideas from her.

Peta laughs. ‘Why would I want to do that?’ she says. ‘I already have friends.’

After recess Miss Agostino has been replaced by Mrs Leeman, which makes me wonder who is taking our class and also, what do I have to do to get away from her? I’m glad we didn’t do the rubbish cheat with Mrs Leeman though; she would have been on to us in a second. She has a sixth sense about that sort of thing.

Mrs Leeman takes us around the side of the administration building and tells us to clean up the grassy area. I look at the area. There’s not one bit of rubbish. No lunch wrappers or dead sports equipment anyway. Just a million of those little white foam balls that come out of beanbags. I know for a fact they’ve been there since I was in Grade 1. Mrs Leeman says, ‘You two need to pick up all these balls before I return at lunchtime.’

She hands us a pair of gloves and a plastic bag each and marches back to the staffroom. I don’t need to turn around to know she’s pulled the blinds across so she can assess our performance through the window.

I look at the foam balls half-buried in the grass.

Is she joking?

It would take a hundred years to pick them all up, not the forty-five minutes allocated by Mrs Leeman. I put my gloves on and try to pick one up but they’re so tiny I can’t even grab hold of it.

I look over at Peta. She hasn’t put her gloves on. She’s pulled the sleeves of her jumper down over her hands and is rubbing them furiously together like she’s trying to make a fire without a box of matches. She must want a detention. Then she grins at me and leans down over the grass, holding her hand flat, close to the little balls. About a hundred of them leap off the grass and cling to her jumper with the static. She goes over to her bag and shakes them into it.

I do the same, but when I try to pick up the little balls they all cling to my hands, face, hair and up my nose. Maybe the old jumper I’m wearing has lost its charge. I’m glad we’re not near any classroom windows. Peta has to demonstrate the technique a few more times before I get it.

After forty-five minutes, we’ve picked up about half the foam balls and Mrs Leeman comes out to check our progress. I can tell she’s impressed. Her mouth has gone from grumpy to kind of neutral. She says we can study quietly in the library until the bell goes at 12.30. I can’t believe it. That’s the equivalent of any other teacher offering a month at Disneyland with five thousand dollars spending money.

Peta and I sign in with Mrs Hillman at the library, wait till she goes into the little office to get something, then sneak out down to the breezeway. Peta wants to check out the mess left from when the pipe burst.

It looks exactly the same. The water level’s gone down but no work has been started. Peta holds up the tape and we both duck under it. She picks up a stick and starts pulling all this stuff out of the pipe. No wonder it burst. There’s heaps of gunk blocking it right where it cracked. We scoop handfuls of mud out. I’m trying not to think about what else has gone through the pipe.

We’re just about to give up on trying to figure out what blocked the pipe when Peta’s stick hits something solid. I hope it’s not a dead rat or something. She reaches in with her bare hands and pulls out a massive branch. It’s more like a tree and it’s attached to a bigger one still in the pipe. There’s a top bit and a million squiggly roots like tentacles all starting to grow through tiny cracks in the inside of the pipe. It takes both of us to get the tree out. It’s not easy because something is all wrapped up in the roots, jamming it in tight. My hands are about to drop off from the cold. At least I hope it’s from the cold and not from some flesh-eating bacteria.

The tree comes out of the pipe followed by a rush of dirty water. It’s totally gross, like watching a giraffe or something being born on TV, only worse because I’m covered in muck and there’s no baby giraffe. There is a bit of grey material, though, and Peta takes it over to the tap to wash off the mud. ‘It might be a bag of cash,’ she says, hopeful. I follow her because I really need to get to that tap myself.

Peta holds the material under the tap. It isn’t a bag and

it isn’t brown either.

It’s blue.

A blue jumper.

With ‘Jesse McCann’ written on the label in permanent marker.

We both stare at it for about five minutes. I can see Peta is impressed by the magnitude of the situation, but I’m completely freaked out.

‘Swear not to tell anyone,’ I say desperately.

‘I can do better than that,’ she says. ‘I’ll help you get rid of the evidence.’

While I stand guard, Peta goes up to the Art Room and comes back with some old newspapers and a plastic bag. I didn’t ask if she had to give anyone an explanation for needing these items.

We wrap up the jumper in several layers of newspaper and put the whole thing in a black plastic rubbish bag. It looks like something from Real Crime Investigation.

‘We need to put it in a wheelie bin off school grounds,’ Peta says, as if she’s done it a hundred times before.

My legs are wobbly climbing over the fence. I’m scared I’m going to crumple up on the footpath and all will be revealed, including the fact that I’ve crumpled up in fear on the footpath. We find a bin and Peta rearranges the other bags in the bin to hide our bag.

She is scary good at doing criminal work.

I’m still no closer to finding out who took my jumper, only where it ended up. The fact that it was the girls’ toilet is all the more mysterious. That means whoever did it really wanted to get me into trouble.

Or is a girl.

Or both.

While we’re cleaning up, Peta must have read my mind because she says, ‘I didn’t put it there.’ I believe her too. Even though she’s a girl and had access to the crime scene.

When I find out who did do it, I’m not sure what I’m going to do yet. Maybe I’ll flush something of theirs down the toilet. But that doesn’t seem like a good idea – the school plumbing isn’t very sturdy.

Peta offers to help me when the time comes. It sounds like she’s looking forward to it.

I want to ask Peta who she’s friends with. I think I’ve seen her hanging around the stairs with Leini and Gina. I don’t mention it, though. Peta knows way too much about me and I only met her this morning. And she helped me solve a problem today. I don’t want to say something wrong and make a new one.

I can’t believe we’re more than halfway through Term 1. Camp is in three weeks. Even less, if you count today. After Mrs Leeman’s daily lecture about keeping away from the muddy trench behind the toilet block, she hands out a massive bunch of permission forms. We have to return them to Mr Winsock by Friday. He must be the camp coordinator this year. I’ll have to see him and tell him I’m not going.

I’ve been so busy wondering how my jumper made its way down the toilet that I forgot all about camp. Camp is a bit like the dentist. You get home and think, Cool. I don’t have to go again till next year … All of a sudden, it’s right there and you have to do it all again. But I hate camp even more than the dentist because it goes for a week.

Even worse is that I can’t tell anyone how much I don’t want to go. Not wanting to go on camp is like admitting you don’t like holidays or ice cream.

Alex comes running over, waving the cabin diagram in the air. ‘If I put you down first and you put Jun down first and he puts me down first we’ll get put in the same cabin, yeah?’

Everyone else is screaming and yelling and waving the camp notices around in the air. I’m screaming on the inside. Mrs Leeman is busy telling Jun he won’t be allowed to go on camp because he’s ruined his camp forms. I look over at his desk. He’s drawn about fifty chickens on his medical form. I don’t know how he did it because we’ve only had the forms for five minutes. It’s an empty threat from Mrs Leeman. Not being allowed to go on camp, I mean. If only it were true.

Jun and Alex are going through the list of gear, working out what they already have. I know without looking we’ve got most of the stuff at home. I try to look a bit enthusiastic but the best I can do is a kind of upbeat neutral.

Mrs Leeman orders everyone to put their camp forms away before she’s forced to confiscate them. Another empty threat.

I wish she’d confiscate mine. The only good thing is … as far as I know, Mrs Leeman has never been on a school camp. She must have a note about it in her file.

I wish it was a note in my file.

The other thing on our desks is our ‘Sneak Peek’ assignment. I got zero. Mrs Leeman said my bee suit idea is ‘ridiculous’ and ‘fanciful’. I don’t even know what she means. I was only going to use ordinary bees. Alex got ‘very good’ for his recycling idea. Jun has a note on his desk to see Mrs Leeman after class.

At least I don’t have one of those.

When I get home that afternoon, I don’t take out my camp notices. I don’t want to bring up the subject of camp and how I plan on not going, because I’m already in trouble for something else. Last week Alex showed me how to do a roundhouse kick he learned at karate and I was practising outside on the deck. I didn’t realise Noah was standing near me until the end bit when you spin around.

I kicked him in the eye.

I don’t know who was more surprised.

Noah says I did it on purpose, but it was just good luck.

I don’t even have that level of accuracy without the spinning around bit.

Dad is still deciding my punishment. He says an accidental action carries a different punishment from one with intent.

The next day at school I return all my blank forms to Mr Winsock and tell him I’ve decided not to go to camp this year.

He makes me come back for a counselling session at lunch, just because I’m not excited about going to the Ovens Valley Recreational Facility with forty-six other kids and four teachers.

The Ovens Valley Recreational Facility. It sounds like a prison.

Mr Winsock says, ‘You’d be missing a fantastic opportunity. You’ll love it when you get there. Give it a try.’

I have given it a try. In Grade 4 and Grade 5. Why do teachers think you don’t know what you don’t like?

He says my parents have already paid the nonrefundable deposit with the excursion fees, so I have to go whether I want to or not.

He’s not a very good counsellor.

He makes me write down all the things I like and don’t like about camp. I write a list because I have to, but this is my real list. The one I’m going to hand in on the last day of Grade 6 along with all my other grievances. I haven’t listed all of them though. I do have other stuff to do.

THINGS I HATE ABOUT CAMP

1. The bus trip. It takes hours and we have to keep stopping because someone (Wesley) has to throw up. Also, the bus always smells funny. Like pool chemicals or something.

2. Sharing a cabin. I can’t sleep with three other kids in a room the size of a cupboard.

3. Camping out for a night. Some people might like sleeping outside in a stinky bag (sleeping bag) that goes inside a bigger, stinkier bag (tent) that has to be assembled first. I prefer to look at the trees and stars and stuff, then go back inside.

4. Orienteering. The strange practice of leaving kids in the middle of nowhere. On purpose.

5. Insects. The further away from civilisation you get, the bigger and meaner the insects are. With insect repellent that is repellent to people only. Last year a bull ant bit me under my arm when I had a T-shirt and a jumper on. It swelled up to about the size of a melon (my arm, not the ant). Mr S said it was my fault for standing next to an ant’s nest … a piece of information that would’ve been handy earlier.

6. Bush tucker night. It’s not actual bush tucker. It’s flour and water mixed together in an ice-cream container. I don’t want to eat something other people have handled, cooked over the fire on a dirty stick. Yuck.

7. Three-minute showers. It takes me longer than that to arrange my stuff on the miniature shelf so that it doesn’t fall on the floor and get all wet.

8. Talent night. We’re put into groups and have to come up with a five

to ten minute ‘performance’ on the last night of camp. No one at our school has any talent for anything so even the name is misleading. Every practice time half the kids make useless stuff out of the craft supplies and the other half don’t do anything.

9. It’s either freezing or boiling. You either have sweat falling in your eyes or it’s so cold you have to wear all your clothes (including pyjamas) at the same time.

10. Journals. The only thing worse than going on camp is having to write about it. I can think of plenty to write about, but we’re graded, so it’s not so much an accurate account as a work of fiction. We could do that from home.

THINGS I LIKE ABOUT CAMP

1. Mrs Leeman won’t be there.

2. Noah won’t be there.

I can’t think of anything else.

I give Mr Winsock a list that doesn’t resemble the above lists in any way and he takes a drink from his promotional Ovens Valley Recreational Facility drink bottle and says, ‘That’s better, Jesse. I knew you’d remember things you like about camp once you wrote them down. Not long to go now!’

I feel like I’m in a recruitment video, but for what I don’t know.

Mr Winsock has finished not helping me, so I head out to find the others. They’re down by the water tanks. Talking about camp.

Braden’s unhappy because he might not be allowed to go on camp.

‘I got into trouble last year at my old school.’ We all look at him.

‘I – we – James and me … we got everyone’s pillow while they were at tea and shoved them all into two sleeping bags … then we left them out in the chicken shed with all the chickens.’

‘How many chickens?’ asks Jun.

‘I’m not sure … about a hundred?’

‘How did they know it was you?’ I ask.

Alex says, ‘Chook poo? I bet it was chook poo!’

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

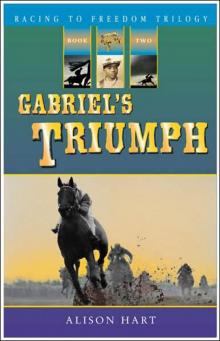

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

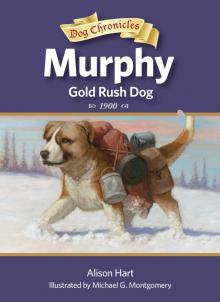

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog