- Home

- Alison Hart

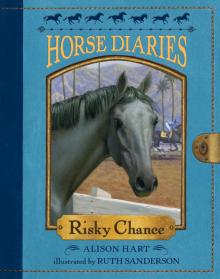

Risky Chance Page 3

Risky Chance Read online

Page 3

“Harrison put Wolf on some crazy two-year-old,” Hughie said, steering me to the right. “Let’s give her plenty of room.”

Suddenly, a horse with no rider charged past us on the left. The reins flapped against his front legs, and the stirrups banged his sides. His eyes were white-rimmed, and he ran as if dogs were chasing him.

I jumped out of his way. As he flew by, hugging the rail, I sensed his fear.

“Loose horse!” Hughie hollered.

Wolf threw a glance over his shoulder. But it was too late. The riderless horse ran smack into the filly. She leaped into the air, flung her body sideways, and landed on the rail. I dug in my hooves, sliding so fast in the mud that Hughie lurched onto my neck.

Legs flailing, the filly flipped over the railing, Wolf clinging to her back. The wood cracked, and I heard someone scream. I glanced toward the outside railing. Marie was leaning over it, staring in the direction of her father.

Hughie screamed, too. He kicked me forward, but I wouldn’t budge. Already the mounted attendants were cantering over. Grooms and workers sped toward the broken railing.

I stood frozen, shaking. On my back, Hughie seemed just as frozen.

The loose horse was still galloping down the track. A mounted attendant cantered after him, trying to head him off. Humans were shouting. A truck rumbled past me and stopped by the broken railing. I rolled one eye toward the outside railing. Marie was gone.

Then Lanny was beside me, his palm on my neck. His eyes were red and watery. “Looks bad,” he said to Hughie.

Without a word, he turned us away from the crowd that surrounded the broken railing. But as we headed back toward the barns, I could still hear Marie’s screams ringing in my ears.

“Stubby’s your jockey in the handicap,” Lanny said a few days later. He was picking out my hooves. All day he’d been fussing over me, and that morning I’d gotten my special mash, so I knew it was a race day.

I poked my head over the stall guard, expecting Hats to be swarming like bees. The aisle was empty except for Barn Cat watching a mouse hole.

Lanny chuckled. “No reporters today. They’re bothering Seabiscuit and Rosemont. But that’s good for us, colt. Odds are twenty to one on you, so no one believes you’re going to win. That means money in my pocket when you cross that finish line first.”

I snatched another bite of hay. Finish line. Yes, sirree. I knew those words well. I had crossed it ahead of every horse in every race. Why should this race be different?

But it was different. The air seemed to vibrate as Lanny led me to the saddling paddock. The crowd was so huge, they hung over the rails.

“There’s Rosemont! There’s Seabiscuit!” rang through the air.

I searched for Marie and her hug but couldn’t find her straw hat and red curls in the crowd. Then Stubby strode into the paddock in place of Wolf.

Where was Wolf? Since the broken railing and the filly flipping, I often heard the word accident. But not one human at the track would say Wolf’s name.

Lanny was frowning as he took the saddle from Stubby. Tall Man had chosen Stubby, and I knew Lanny didn’t like the jockey. When he boosted Stubby into the saddle, the only thing he told him was, “No whip.”

Then Lanny stroked my nose. “Sixty thousand people are here watching this race, colt. But you know what to do.”

We headed from the paddock in the post parade. I broke into a trot. Stubby took up the reins. Too tight, I tried to tell him by rooting my head. He only firmed his grip.

So I pushed Stubby out of my mind. I missed Wolf’s light touch, but I also knew how to run and win without a jockey telling me what to do. I knew how to leap clean from the starting gate and charge to the front. That way mud and dirt didn’t get kicked in my face. That way I didn’t have to weave through the slow horses or get boxed in by crafty jockeys. And I always had a burst of energy in case a hotheaded runner tried to catch me.

I know how to win this race, yes, sirree.

I was the last to enter the starting gate. I danced in the chute, ready for the bell. Stubby was talking to the jockey next to him. “The track’s like goo, Harry,” he was saying. “Seabiscuit’s got the worst footing in number three. We’ve got the best in seventeen and eighteen.”

Just then, the bell rang. I was ready. Stubby was not. His fingers weren’t twined in my mane, and when I shot from the gate, he fell back into the saddle. The bump threw me off balance. I went down, my front legs folding beneath me. Instantly, I leaped up and charged after the fleeing pack of horses.

Pain stabbed my front right leg. Stubby had righted himself. But we were lengths behind the last horse.

Ignoring the pain, I ran faster than I had ever run before. I flew past several horses that lagged at the back. Dirt clods pelted me as I galloped around the first turn. The other horses were packed against the railing, so I ran on the outside. Slowly, I gained.

Faster. Faster. I drew ahead of two more horses. Up ahead, I spied the area where Wolf had had his accident. The railing was fixed, but I knew. For a second, I hesitated.

Whap. Whap. I felt stings on my flank and heard smacks on my hide. Stubby had a whip.

Over and over, his arm rose and fell. I flicked my ears, trying to ignore the ache in my right leg and the slaps on my flanks. Tried to forget about the runaway horse and the filly flipping over the railing. Tried to think only about winning.

Run. Run. Faster. Faster.

Only five more horses ahead of me. I can do it.

Finish Line

I pummeled the track with my hooves. I charged past the middle set of horses and down the homestretch. The finish line was in sight. I was gaining on the front runners. Then, suddenly, the pain in my leg shot through me like fire, and I stumbled.

The crowd roared as the two lead horses crossed the finish line, neck and neck. Cries of “Seabiscuit” and “Rosemont” filled the air.

Gamely, I crossed the finish line, too. In an instant, Lanny was there. Grabbing my reins, he practically dragged me to a halt.

Anger twisted his face. He snatched Stubby’s leg and jerked him from the saddle. “Why didn’t you pull him up?” he screamed, shaking the jockey by the shoulders. “Why did you whip him? Couldn’t you tell the horse was lame?”

“Hey! Hey!” Two men separated Lanny and Stubby. Then Trainer was there with the vet.

I was blowing, and my sides heaved. The pain made my eyes roll. Lanny tried to support me while the vet inspected my front right leg. “Feels like the colt bowed his tendon,” he said, shaking his head. “Let’s hope it’s sprained and not torn.” Rummaging in his bag, he pulled out padding and tape.

Lanny took off my saddle. After he threw it to Stubby, Lanny shoved him. Trainer and the vet had to hold Lanny back as the jockey hurried off.

Quickly Lanny stooped and wrapped my leg with padding and then taped it. He led me down the track, walking slowly while I hobbled beside him.

To my right, I could see the winner’s circle crowded with people. A dark horse wore the blanket of roses. I saw the flashes and heard the shouting. “Rosemont! Rosemont!” rang out. This was the first time I wasn’t the horse posing for the cameras. And as we passed by, no one was interested in me.

* * *

They sent me back to the farm, where Lanny tended me for many days and nights. He hosed my leg, iced it, rubbed medicine on it, wrapped it, and walked me. Slowly, the pain left. Slowly, I stopped limping.

And slowly, I forgot about Wolf, Marie, Santa Anita, and racing to win.

March 1938

Spring came and I was turned out in a small pasture. My leg felt good enough that I could canter along the fence line. I’d whinny at the yearlings, challenging them like in the old days. In the beginning, they would win. Then I began to beat them.

Oscar again started working me on the farm’s track. When I breezed, my leg felt strong, and the urge to run bloomed within me.

One hot day, Lanny came to the pasture where I grazed. His eyes glimmere

d as he stroked my nose before leading me into the barn. He groomed me as always, but there was no humming. When he was finished, he ran his gaze over me as I munched my hay. Then he shut the stall door and hurried away, his head ducked low.

I whinnied to him, but he didn’t turn around.

I was finishing my hay when I heard people come into the barn. I popped up my head, hoping it was Lanny returning. But it was Trainer and a man shaped like a rain barrel.

“Winner of eight stakes races,” Trainer was saying. “He’s ready to win again.”

Barrel Man grunted a laugh. “You mean Davidson wants to dump him, so he’s entering him in a claiming race at Tanforan.”

Race! My ears pricked. I was going to race again!

Trainer shrugged. “Colt has a bowed tendon. It’s healed, but the vet says it’ll probably bow again. So yeah, Davidson wants to dump him but make some money, too.”

“Gotcha.” Throwing open the door, Barrel Man walked in with a lead line. There was no pat, no hello. He clipped the rope on my halter and led me out to a van.

I balked at the bottom of the ramp. Where was Lanny? Then I heard a whicker from inside the van. Dappled Filly?

Hurrying, I clattered up the ramp. The inside of the van was dark. Barrel Man tied the rope to a ring. For a moment, I was able to see the light-colored horse tied next to me. Her backbone stuck up, and her coat was dull, but when we touched noses, I knew it was Dappled Filly.

The ramp shut with a clang, and we were in darkness. We whiffled excitedly, but then the motor roared, the van lurched, and I spread my legs to keep from falling. We rumbled down roads for what seemed forever. Finally the van squealed to a stop.

I smelled horses. Were we back at Santa Anita? Would Lanny, Wolf, and Marie be there?

The ramp lowered, and light poured into the van. Barrel Man led me down the ramp. I blinked as I looked around, immediately realizing this was not Santa Anita. Turning, I looked for Dappled Filly. A groom was tugging her down the ramp. She walked carefully, as if her feet hurt. Raising her head, she whinnied at me, but her eyes were as dull as her coat.

“This steel-gray colt looks good,” Barrel Man said, pointing at me. “Maybe he’ll win a few. This light-gray filly, though …” He frowned. “Sweet Dreams. I’ll bet she’s done for.”

Sweet Dreams. I like that name. I whinnied back at her, trying to tell her that it was okay, but the groom took her away.

Barrel Man led me into a stall. It was bedded with straw and the hay smelled fresh, but there was no Barn Cat, no Lanny, and no Stakes Horse. All down the shed row were claim horses, and it didn’t take me long to realize that I was a claim horse, too, and that my life would change forever.

* * *

At Tanforan, I won my first race on a Wednesday and my second race on a Saturday. Strutting into the winner’s circle, I was greeted with cameras popping. Not as many as before, but still, it felt good to be galloping and winning again. The only thing missing was a hug from Marie. But after my third race, when I walked from the winner’s circle, a strange man took off my bridle and put a different halter on me.

“Risky Chance, you jest won me a hun’erd dollars,” the man said as he spit something on the ground. “Tomorrow you’ll win me a hun’erd more.”

He led me to a different barn. A groom bathed me and walked me until I was almost cool, then tossed me in a stall. It didn’t have straw bedding and the hay smelled musty, but I was hungry. When I poked my head over the stall guard, the horses on either side of me pinned their ears. Both had tired, hungry eyes.

I searched for Dappled Filly and neighed for Lanny. Nobody answered.

The next morning, a groom brought me a bran mash. My insides rumbled, and I ate every bite, licking the pan. At Santa Anita, mashes meant race day. Only I had just raced yesterday. Perhaps New Owner was nice after all and gave his horses mashes every day.

After I ate, a groom came in and brushed me until I shone. He combed my mane and buffed my hooves. Not so bad, I thought. Maybe I had lucked out with New Owner.

But that afternoon, the groom led me to the saddling paddock, and I realized this was race day. At Santa Anita, Lanny gave me lots of days to rest between each race. Obviously, New Owner didn’t agree. In the saddling paddock, I saw the horse stabled on my right. When he walked, there was a slight hitch in his gait as if he hurt.

New Owner was there, talking to a jockey. “This horse won his last race,” he was saying. “Push him to win. I’ve got big money riding on him.” He handed the jockey a whip and boosted him into my saddle.

I eyed that whip. I felt the iron grip on the reins. I switched my tail to show my anger, but the jockey tapped me with the whip as if to show me who was boss.

The bugle sounded, we headed for the post parade, and I forgot about everything but winning.

Done For

Rain misted on us as we paraded past the grandstand. The track was soggy, but I didn’t care. The field of horses would be easy to beat. Too many acted sore or worn-out. Then I spotted Dappled Filly. She trotted past me with high, frantic steps. Her eyes were white-rimmed. As she went by, I nickered to her, but she seemed not to hear—or to care.

“Chance!” Someone called my name. I halted, sliding in the mud. A boy hung over the inside railing. He wore a cap and overalls. A short man stood beside him. His face was pale, and he leaned on sticks. Who were these humans? I lifted my head to catch their scent.

Whap! The whip struck me hard. “Git up!” the jockey growled, and I bounded forward.

I broke clean from the starting gate, but still the jockey whipped me. My ears pinned tight in anger, and I ran that race with only half my heart. Partly because I hated that whip, but also because of the heat that began in my leg. When I crossed the finish line in third place, I looked for Dappled Filly. She straggled in last. Foam dotted her mouth, and her head hung. What had happened to the high-spirited horse who used to race me neck and neck?

“Filly’s done for,” her jockey said as he dismounted.

I neighed, calling out to her, but she disappeared in the milling horses and riders.

New Owner’s face was red when he hurried up. “This horse should’ve won!” he exclaimed. “What in thunder happened?”

The jockey snorted. “He only came in third because the rest of the field was half-dead. I had to whip him four times. Something’s off. You need to check his right front leg.”

“Horse is as sound as my grandmother.”

“Then your grandmother must use a cane,” the jockey said as he dismounted and took off his saddle.

“Well, it doesn’t matter if he is lame,” New Owner said. “Horse won me some money, and he’s been claimed. He’s someone else’s problem now.”

And so, tired and sore, I was led to another barn.

I was hungry and sweaty after the race. But a skinny groom about the size of a broom handle barely walked me, and the spray from the hose was cold. When he led me into a stall, I found old hay and no warm mash.

That night, another owner came in. Smoke swirled around his head. Bending, he felt my legs. “Horse is lame,” he said gruffly. “I should have known not to claim a horse from that crook Bugsy. Ice him. Rub him with liniment. Wrap him. Hand-walk him tomorrow. And put some of this in his feed.” He handed the groom a packet. “I want him racing sound in three days.”

The skinny groom tried. But he was as hungry and tired as I was. He put the white powder in my grain but forgot to ice my legs. He slathered on liniment, and then wrapped the bandages so tight that my leg swelled.

The next day, Gruff Owner’s shouting could be heard up and down the shed row. He cuffed the groom and told him to get packing. Then he wrapped the leg himself. “You’re costing me money, horse,” he muttered as he worked. Standing, he put more powder in my grain. It tasted bitter, but I was so hungry I ate it anyway.

On race day there was no mash.

For what seemed forever, I stayed in Gruff Owner’s barn. On race days my legs were wra

pped. I ate white powder in a handful of grain. Rarely did I get out of the stall for a gallop. Never was there sweet hay or kind words. My muscles grew stiff, my ribs thin, and I could barely stand on my right leg. I hadn’t won a race in ages.

“You’ll need to use this.” Gruff Owner handed the jockey a whip for my next race. “Horse is slow. He’s got no fire. Only thing he’ll understand is the sting of a whip.”

“I’ll make him run,” the jockey said.

The jockey whipped me from the starting gate to the final pole. I crossed the finish line last. By the time the jockey dismounted, welts had puffed up on my flank and rump.

My head hung as low as Dappled Filly’s the day she’d lost her race. Not because I was ashamed that I was last. Not because clods of dirt from the other horses had pelted me in the face. Not because my neck and chest were sweat-crusted.

I hung my head because of the emptiness of my heart. I no longer cared about winning.

“Thank the stars some sap finally claimed him,” Gruff Owner said when the race was over.

“Lucky for you,” the jockey told Gruff Owner as he took off the saddle. “Not so lucky for the sucker who claimed him. This horse is done for.”

Done for. That’s what the jockey had said about Dappled Filly.

Gruff Owner pulled off the bridle and put on the halter. He led me toward two people coming onto the track. I recognized them. It was the short man who walked with sticks under his arms and the boy wearing overalls.

I turned my head away. By now I knew what would happen. I was a claim horse. That meant no special person owned me. Even worse, the man and the boy would soon discover I was done for.

What would happen then? What happened to horses who could no longer run and win?

I thought of Dappled Filly and shuddered.

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

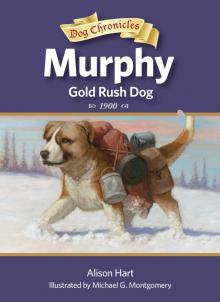

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog