- Home

- Alison Hart

Bell's Star Page 2

Bell's Star Read online

Page 2

Katie ran ahead and into the barn. When she waved, I trotted through the wide doorway.

I halted, and Eliza slipped off. Quickly, Katie led her behind the hay mound, which was low because of the long winter.

From the corner of the barn, Patsy the milk cow watched us. Bell stared at us from her stall. I wanted to tell my mother what was going on. I wanted to ask her if she knew the words runaway, slave, and Canada. But I heard Papa's boot steps outside the barn.

“Katie!”

Katie shot from behind the hay mound, scaring the chickens scratching in the dirt. I trotted into my stall. Grabbing a brush, she hurried in after me just as Papa marched into the barn. His face was red, so I knew he was angry.

“Where have you been?” Papa asked. “It is past supper. Your mother has been worried.”

“We were at the river,” Katie explained. “Star and I were so hot and muddy. We wanted to wash off.”

Papa looked over the stall door, his dark brows raised. Katie's pinafore was as speckled as a white and brown hen. I was muddy from my stockings to my chest.

He frowned at her. “The truth, my daughter?”

“We fell in the river,” she said sheepishly. “I'm sorry, sir.”

Papa sighed. “Groom Star carefully. Feed him extra corn. Tomorrow he has to plow.”

Corn I knew, and my mouth watered excitedly. Plow I also knew from my mother's work last year. That did not excite me.

Papa pointed a finger at Katie. “And you will help, too.”

“But I'll miss school,” Katie said.

“That is your punishment for leaving your mama. She had to unload the sap alone while you frolicked in the river,” he said.

Katie hung her head. “Yes, sir.”

“Mama left supper on the table,” Papa said. “So be quick about your chores.”

As soon as Papa left, Katie fed me a bucket of corn. Then she shook out Bell's old saddle blanket and took it to Eliza.

When Katie was finished, she kissed my nose. “I'll return when it's safe. I promised Eliza I'd help her find her mother. Will you help me keep that promise?”

I chewed my corn, not sure what my mistress was asking. When Katie left, I joined Bell at the back of the stalls. We could see Eliza, who was curled up in the hay. The blanket was wrapped around her and she was fast asleep. Who is this strange human? my mother asked.

I told her all that had happened, puffing my chest a bit when I spoke of the rescue. Then I asked, What are runaways, slaves, and Canada?

I only know what I hear when I go to school with Katie, she said. Katie's teacher says slaves are humans who are not free. They can't go to school. They work all day. Sometimes they're whipped. Runaways are humans who want to be free. Some run north to Canada. There they can be free.

Thinking about my mother's words, I went back to my feed bucket and licked up the last kernel. I knew about north, work, and wanting to be free. And I had seen Mr. Jenkins whip his mule, Tansy. The crack of the whip made me shudder even now.

I understood why Eliza had run away and why she wanted to be free. But I had never heard of Canada. Was it so different from our farm? And if I went north, I wondered, would I be free, too?

The Sheriff

The next day, before it was daylight, Katie crept into the barn. She had a basket in her arms.

Patsy mooed for her morning hay. I started to whinny for my corn. But Katie put a finger to her lips. Without even glancing at the corn bin, she disappeared behind the hay mound.

Eliza had been so quiet all night, I'd forgotten about her. Now I turned in my stall to see behind the mound. The two girls sat in the hay, sharing food from the basket. One of Katie's shawls was around Eliza's shoulders.

Bell stirred in her stall. She'd been lying down, sleeping. Now she stood and shook. Why is Katie here so early? she asked.

Not to feed us, I grumbled. I kicked the wall, reminding Katie she should share some hay with Patsy, my mother, and me.

Katie jumped up. “Don't be so impatient, Star.” Picking up the pitchfork, she tossed a forkful of hay to each of us. Then she went back to Eliza.

“As soon as it's light enough to see, we'll leave,” Katie said. “You can ride Bell. She's gentle. I'll lead you across the river to the road north. Perhaps your mama will be waiting.”

Eliza nodded as she hungrily ate a biscuit. Then she swallowed. “Won't your papa be angry if you leave?” she asked.

“I'll tell him that Star ran away and I had to ride Bell to catch him.”

I popped my head up. Hay dangled from my mouth. Run away? That sounded fun.

“You would do that for me?” Eliza asked.

“Yes.” Katie nodded. “It's a lie, I know. And if Papa finds out, I'll have to help plow for a fortnight. But you need to be with your mama. You need to be free.”

Standing, Katie picked up the basket. “And I need to tack up the horses. Come. You can meet Bell.”

Katie took my bridle off the wooden peg. When she opened my stall door, I put my head in the corner. I did not want to be bridled so early. I wanted to finish my hay!

But then I remembered how Tansy had been cut with the whip, and I did not want Eliza whipped, too.

Katie put the metal bit in my mouth and slipped the headstall over my ears. Then she gave me a big hug. “Thank you for helping, Star.”

Eliza was in Bell's stall. She was timidly patting her neck. My mother snuffled her gently, telling her not to be afraid.

Katie opened my stall and led me to the barn door. The sky was turning light, but fog had settled in during the night. I saw the glow of a candle in the window of the house and heard someone cough from inside.

“Papa's awake,” Katie whispered. “We have to leave now.”

Katie dropped my reins to help Eliza with Bell. I pricked my ears, suddenly hearing the thud, thud of a horse's hooves. Someone was coming up the lane!

Was it danger? I pawed the ground, trying to warn Katie. “Be still, Star,” Katie called from inside the barn.

Tossing my head, I peered out the barn door. The air was thick with fog, but I could smell a horse. It was Dover, the horse belonging to the human called the sheriff. Why is the sheriff here so early? I wondered. I whinnied to Dover, and he whinnied back, alerting Katie that someone was coming.

“Hide, Eliza!” Katie cried out.

I heard the scampering of feet behind me and the slam of Bell's stall. Then the front door of the house opened, and Papa came onto the step. Holding up the lamp, he tried to see through the morning mist.

“Katie? Are you in the barn?” he called.

“Yes, Papa.” Katie hurried to stand beside me. “I was feeding Star. I knew you wanted to start plowing early.”

Just then Dover and the sheriff appeared through the fog.

“Morning, Miss Katie,” the sheriff greeted her. “Morning, Hiram,” he called to Papa on the step.

“Morning,” Papa called. “What brings you to our farm this morning? I hope it isn't bad news.”

“Not bad news, Hiram.” The sheriff dismounted.

Dover snorted, and I snorted back. Dover was a strong Morgan horse, too. He carried the sheriff from farm to farm. I tugged on the reins in Katie's hand. Horses are herd animals, so we love to meet others of our kind.

Katie led me toward Dover and we touched noses. Dover and I squealed and Katie scolded us. “Hush,” she whispered. “I want to hear what the sheriff tells Papa.”

“I'm riding to all the farms along the river,” the sheriff said. “I received a telegraph yesterday concerning runaway slaves, a mother and daughter, traveling through Vermont into Canada.”

I felt Katie tense beside me. Hooking her fingers into my mane, she held on tightly.

“The mother and daughter were seen crossing the river below town,” the sheriff continued. “A witness said the daughter was swept downstream.”

“I've seen no runaways,” Papa said. “And like most Vermonters, I don't agree with slavery. Let them

run to freedom, I say. All people should be free.”

The sheriff nodded. “I know how folks in this area feel about slavery,” he said. “But the new law says we have to help return them to Southern owners.” He pulled out a paper from his saddlebag. “The telegraph states there's a reward. One hundred dollars for any information leading to the capture of the runaway slaves Honesty and Eliza.”

Runaways. Eliza. I knew those words. But I had never heard of law or reward.

“A hundred dollars is a mighty sum,” Papa said. “The winter was hard. That reward would buy seed and pay debts.”

Katie gasped. “Papa! You wouldn't trade a person for seed!”

“Hush, daughter. This is a matter for grown-ups,” Papa said. “Not that the reward concerns us. We have no knowledge of the runaways.”

“Let me know if you hear or see something,” the sheriff said. “It's better that folks in Vermont catch the mother and daughter. At least we'll treat them with kindness.” He held up the telegraph. “The Southern owner has sent slave catchers after the runaways. They're arriving by railroad this morning.” The sheriff frowned at Katie. “Slave catchers aren't like us, Miss Katie. No telling what they'll do if they catch those two.”

Katie turned white. I nudged her shoulder, thinking about Eliza hiding behind the hay mound. If Papa knew she was in the barn, would he turn her in? I wondered. And even worse, Who are these humans called slave catchers, and what will they do if they catch Eliza?

Slave Catchers!

Tipping his hat, the sheriff said, “Thank you for your time, Hiram. Send word if you see those runaways.”

Papa nodded. “I'd like to be of help, but as I said, there has been no sign.”

The sheriff mounted Dover. “I'm off to see Miss Biddle. Rumor around town says she's one of the folks who help runaways escape.”

“Miss Biddle? My teacher?” Katie asked.

I knew the human Miss Biddle. She fed me dried apples when I went to school.

“Yes, miss,” the sheriff replied. “Rumor has it she's helped more than a few slaves find their way to Canada. Now I best be on my way,” he said. He reined Dover around, and they trotted off.

Papa waved farewell and then shook his head. “Miss Biddle is foolish.”

I could feel Katie's arm shaking against me. Was she afraid for Eliza? But then she stamped her foot like an angry horse.

“Miss Biddle is not foolish,” Katie declared. “She's right. Slaves are people, too. They should be free. Please don't help the sheriff, Papa.”

Papa shook his head. “You are too young to understand, daughter.” He blew out the flame in the lantern. Setting it on the step, he headed to the barn. I whinnied to Bell, letting her know that Papa was coming. Would she warn Eliza?

Patsy mooed hungrily. Katie and I trotted into the barn after Papa. Dropping my reins, Katie quickly ran to the hay mound to give Patsy another forkful of hay. “There, Papa. Patsy is fed.”

“Thank you, Katie. You are being very helpful this morning.” While Patsy chewed, he pulled the stool over to milk her. “So, daughter, why is Star bridled?” he asked as the milk squirted into the bucket.

Katie flushed red. Does Papa know our secret? I wondered.

I glanced uneasily at the hay mound. There was no sign of Eliza, and Bell was calmly eating the last stalks of her hay.

“Umm, well, I hoped to ride Star before plowing,” Katie said.

“You mean you hoped to race him wildly through the fields,” Papa said.

“Yes, sir.”

He sighed. “Daughter, life is hard work. Don't you think I'd rather race than plow? Farmer Harvey boasts that his Thoroughbred, Liberty, can beat any Morgan horse in the county. Don't you think I'd like to prove him wrong?”

I tossed my head excitedly. Racing! Why, Katie and I had already beaten Billy Barton and his Thoroughbred, Prince. Like many Morgans, I'm only fifteen hands high, but I'm as fast as lightning.

Katie perked up. “Oh, can we, Papa? Star can beat that old Liberty any day!”

Papa sighed again. “No, Katie. What if Star got a stone bruise or broke his wind? How would we plant spring crops? How would we clear the new potato field?”

“I understand, Papa,” she said.

“Harness Star. Then run into the house. Mama's putting noon meal in a basket. We'll be in the fields all day.”

All day! I knew what all day meant. It meant I would be stiff and sore when we trod home at dusk. It meant no splashing in the river or galloping wherever we wanted. And it meant that we wouldn't be able to help Eliza find her mother.

Katie's shoulders fell, so I could tell she knew what it meant, too. “Yes, sir.” Katie walked over to the pegs. As she lifted the harness, she asked, “Papa, what are slave catchers?”

“They are men paid to hunt runaway slaves,” he replied. “When they catch the slaves, they take them south to their owners.”

“What if they don't want to go back? What if they want to be free?” she asked.

“Slaves belong to their owners,” Papa said. “That is the way in the South. They cannot choose to be slave or free.”

“That is wrong,” Katie said. “And if I met a slave, I would be like Miss Biddle and help her run to freedom.”

Papa stood up so fast the stool fell over. “You would not!” He shouted so loudly that I startled and Katie dropped the harness. “The new law says that no one can help runaways.” He pointed his finger at Katie. “And that includes fathers and their meddling daughters.”

Picking up the milk bucket, he added sternly, “There will be no more talk about runaways. Finish your chores. We leave for the field in ten minutes.”

As soon as Papa left, Katie scurried behind the hay mound. I could hear her whispering to Eliza. I heard promise, tonight, and north. Katie was as stubborn as Tansy the mule. I knew that despite Papa's harsh words, my mistress would soon be helping Eliza.

The warm sun shone upon my back. I plodded in a straight line, straining against the harness as the plow blade cut through the hard dirt. A pesky black fly settled on my rump, and I wiggled my skin and switched my tail.

Behind me, Papa guided the plow. I swerved to shake off the fly. “Gee,” he called, telling me to move right. “Haw,” when I went too far.

Behind Papa, Katie walked in the new furrows. Bending, she picked up stones and rocks. She carried the large stones to a pile for fencing. The small ones she tossed in a sack.

The three of us had been working all morning.

The fly bit me and I kicked out. Papa hollered at me to settle down. I snorted, tired of the stinging flies, the endless back and forth, the chafing harness, and the sun.

When will it be time to race to wherever I want? I wondered. And more importantly, When will it be time to rest?

Finally Papa said, “Noon meal, Katie.” He unhitched the trace chains and steered me to the shade of a pine tree. The pungent smell of the needles helped keep the flies away. The shade cooled my back. A bucket of water waited for me; a basket waited for Papa and Katie.

Katie followed us, the sack of stones banging against her skirt. Under her bonnet, her face was as sweaty as mine and a fly bite swelled on her cheek. She took the bit from my mouth so I could drink.

Papa opened the basket. He handed Katie a baked sweet potato, its skin orange and wrinkly. I eyed it with interest, and Katie fed me a morsel. It was cold and sweet.

“You best eat, daughter,” Papa said.

“Star needs it more than I,” Katie replied. “He's been plowing all morning.”

“And you've been picking rocks all morning.”

“You always say that a family needs to share the chores—and the food,” Katie said stubbornly. “And Star is part of our family.”

Family. I liked the sound of that word.

Papa frowned, so I thought he didn't like the word, but then he laughed. “Daughter, you and Tansy the mule must be cousins.”

Holding out her palm, Katie fed me a corner of her ho

ecake. Just then I heard the sound of hoofbeats coming from the direction of the farm. Was my mother coming to visit?

Two strange horses cantered over the hill. Papa spotted them, too. He stood, shading his eyes.

“Who's that?” Katie asked as she jumped to her feet.

“I don't know,” Papa said. “They're not neighbors or townsfolk.”

Raising my head, I whinnied. The horses did not whinny back.

“Step behind Star, Katie,” Papa said as they cantered closer, and Katie hid herself by my off side.

Papa stood beside me and placed his hand on my neck. Two men rode tall in the saddle. They held the reins tightly, and their horses tossed their heads as if the bits hurt their mouths.

The men pulled their horses sharply to a stop. The horses were as long-legged as Liberty the Thoroughbred. I saw marks on the sides of their bellies from their riders’ sharp spurs. One of them held a whip.

“Good afternoon, gentlemen,” Papa greeted them.

The taller man asked, “Are you Hiram Landry?”

“Yes, I am,” Papa replied. “How can I help you?”

“We're hunting for two runaways seen crossing the river yesterday. A witness said one of them, a girl, was swept downstream.”

Papa nodded. “So the sheriff told me this morning.”

The taller man spat on the ground. “Your farm is downstream from there. We aim to hunt for her here.”

I flicked my ears, hearing mean in the man's voice. The smaller man's horse pawed nervously, and his rider yanked the reins.

I felt Katie creep closer to my head. Turning, I blew softly on her shoulder. Flipping back her bonnet, she cupped her palms around my muzzle. “Those men must be the slave catchers who want Eliza,” she whispered. “But, Star, we have promised to keep her safe. And we must keep our promise!”

Katie's Plan

“Who's that hiding behind the horse?” the tall man hollered. “Show yourself!”

Gabriel's Journey

Gabriel's Journey Whirlwind

Whirlwind Anna's Blizzard

Anna's Blizzard Emma's River

Emma's River Gabriel's Triumph

Gabriel's Triumph School Rules Are Optional

School Rules Are Optional Bell's Star

Bell's Star Gabriel's Horses

Gabriel's Horses Finder, Coal Mine Dog

Finder, Coal Mine Dog Shadow Horse

Shadow Horse Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I

Darling, Mercy Dog of World War I Risky Chance

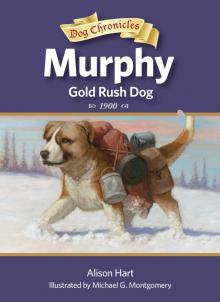

Risky Chance Murphy, Gold Rush Dog

Murphy, Gold Rush Dog